How Games Do Destruction

Break, bend, blow up

Hey. I’m Mark. Let’s talk about destruction.

Let’s talk about smashing cars and levelling buildings. Let’s talk about terrain deformation and fire propagation. Let’s talk about games where things can break and bend and blow up.

But I’m not talking about those fancy pre-canned animations that play as part of a cutscene or scripted moment. I’m not talking about buildings that fall down in the exact same way every single time.

I’m talking about doing destruction in real-time. In response to a player’s actions. As part of the gameplay.

That’s a whole ‘nother thing. That’s really hard.

And it’s hard because you’re dealing with unpredictable physics and particles and lumps of debris and if you’re not careful... you’ll tank the frame rate.

And so that’s what I find interesting about this topic. Doing dynamic destruction in games is about being clever. It’s about using cost-cutting algorithms and outright magic tricks to blow up the world, without blowing your memory budget.

So in this post I want to look at 6 games that have done destruction in wildly different ways - and reveal the ingenious techniques they’ve used to make their worlds fall apart.

I’m Mark Brown. This is Game Maker’s Toolkit. And here’s how games do destruction.

Control

Okay - let’s start with Control.

This is a game where the environment just falls to pieces as you play. Your bullets rip through tables and chairs. And you can use Jesse’s telekinetic powers to rip chunks of concrete out of the wall.

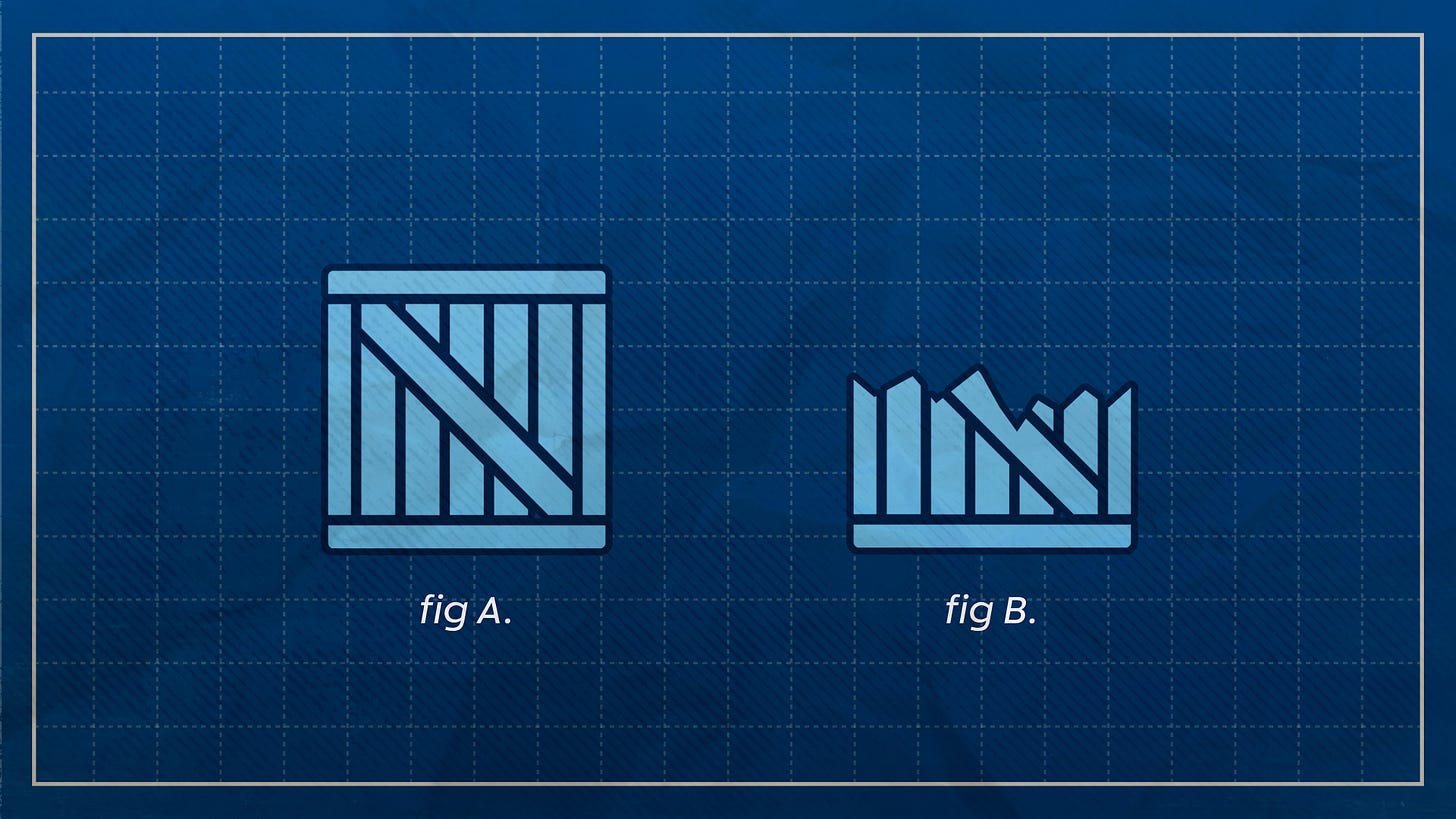

Now this is perhaps the most common kind of destruction in games - almost every shooter is filled with props and small objects that can be broken upon impact. And they all use basically the same technique.

You store two versions of the object in the memory - an intact one, and a broken one. And then when that object is attacked you replace A with B. It’s simple, but it works.

And Control uses the same idea - it just takes it a lot further.

For one, objects are made up of loads of individual pieces that can all be destroyed independently - that means objects can break at almost the exact point where you attack them.

And because those broken pieces are distinct physics objects that are connected with joints - well, if you break a table in half then the table will fall into two parts and collapse in a realistic way.

The game will also play a particle effect when the object breaks to cover up the transition. Props are tagged with different materials like metal, concrete, and wood - and will then play a specific effect on impact.

And finally - decals are used to really sell the impact. Decals are basically stickers that you can slap on the environment - like bullet holes and craters. And control has some really good ones that trick you into thinking that you just made an actual dent in the wall.

Put all of this together and you get an environment that is chaotically crumbling around you in a truly satisfying way.

Astro Bot

Next - let’s talk about Astrobot.

So I just said that the way to do destruction is to secretly prepare a broken version of whatever object you want to destroy. But it turns out that you don’t have to fake the fracture.

So in AstroBot, there are these logs that you can cut with your little laser tootsies to make smaller logs. And they seem to cut exactly where you damage them. What’s going on there? Does the game just have thousands of possible variants of this log, tucked away in memory, ready to swap out?

Turns out - no. The game actually projects a flat 2D plane, underneath Astro Bot, and literally divides the 3D model at the place where you cut it. It then adds new edges and surfaces, creates new collision shapes, and spits out two models to represent the cut logs. All in a single frame.

This is also how Rainbow Six: Siege lets you shoot through walls: it slices up the model in real time. It’s the tech behind Hardspace: Shipbreaker - a game where you use a big ass laser cutter to slice up bits of spaceship. And it was even being used in Red Faction back on the PlayStation 2 to dynamically cut spheres out of the walls.

This turns out to be quite expensive on the hardware, so it comes with limitations. It only works on simple shapes, and the games will typically hide the broken pieces after some time to avoid clogging up your memory. But still: in certain circumstances, you can do the destruction in real-time, instead of preparing it in advance.

BeamNG.drive

Okay, so physics objects in games typically use something called rigidbody physics. Which means they always retain their exact, rigid shape. But other games use soft body physics to create something more malleable and bouncy. It’s the technology behind squishy games like World of Goo and Jelly Car.

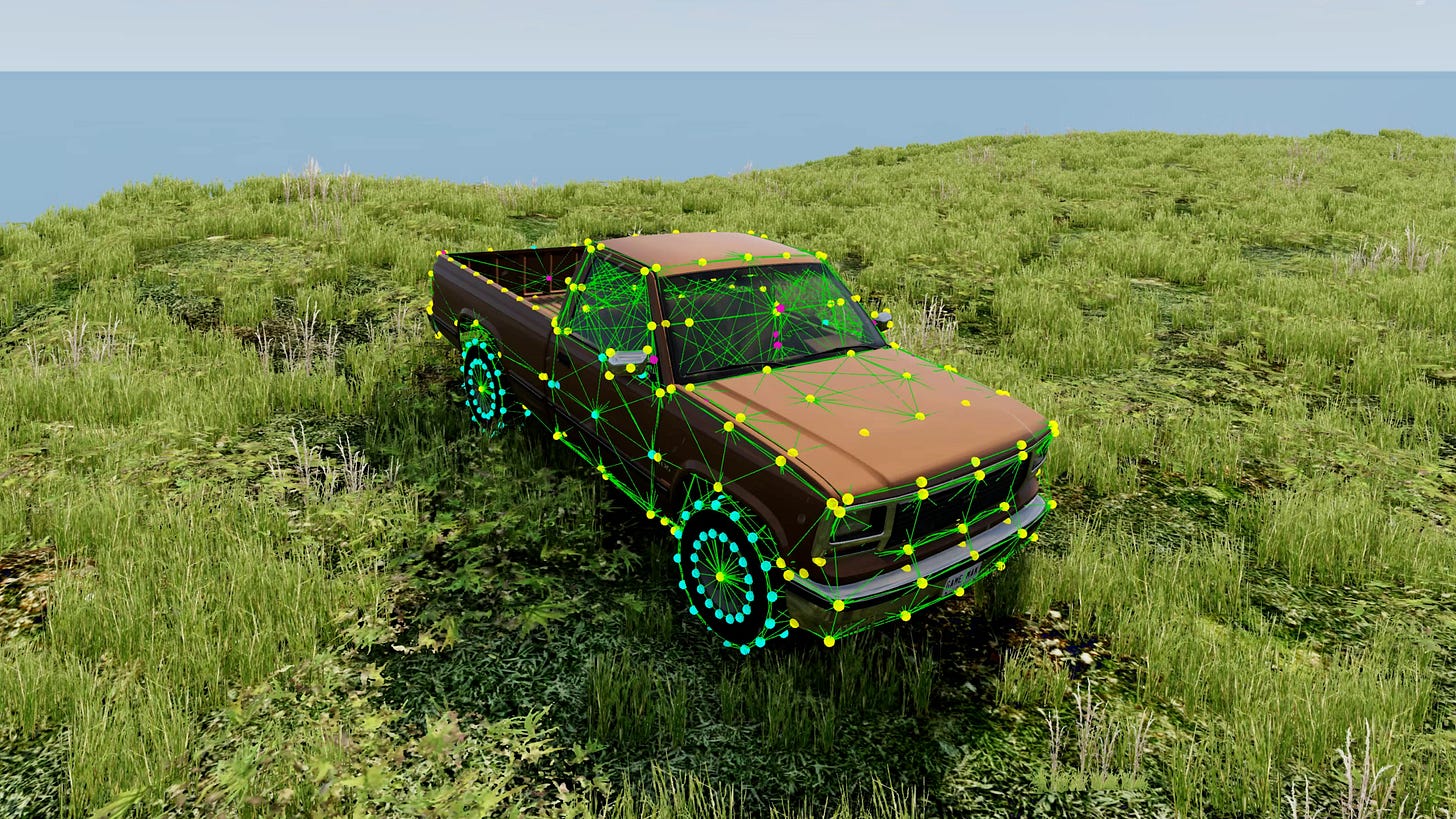

And this idea can be scaled up to create a realistic vehicle - as seen in BeamNG.drive - which can lead to extremely detailed and realistic deformation.

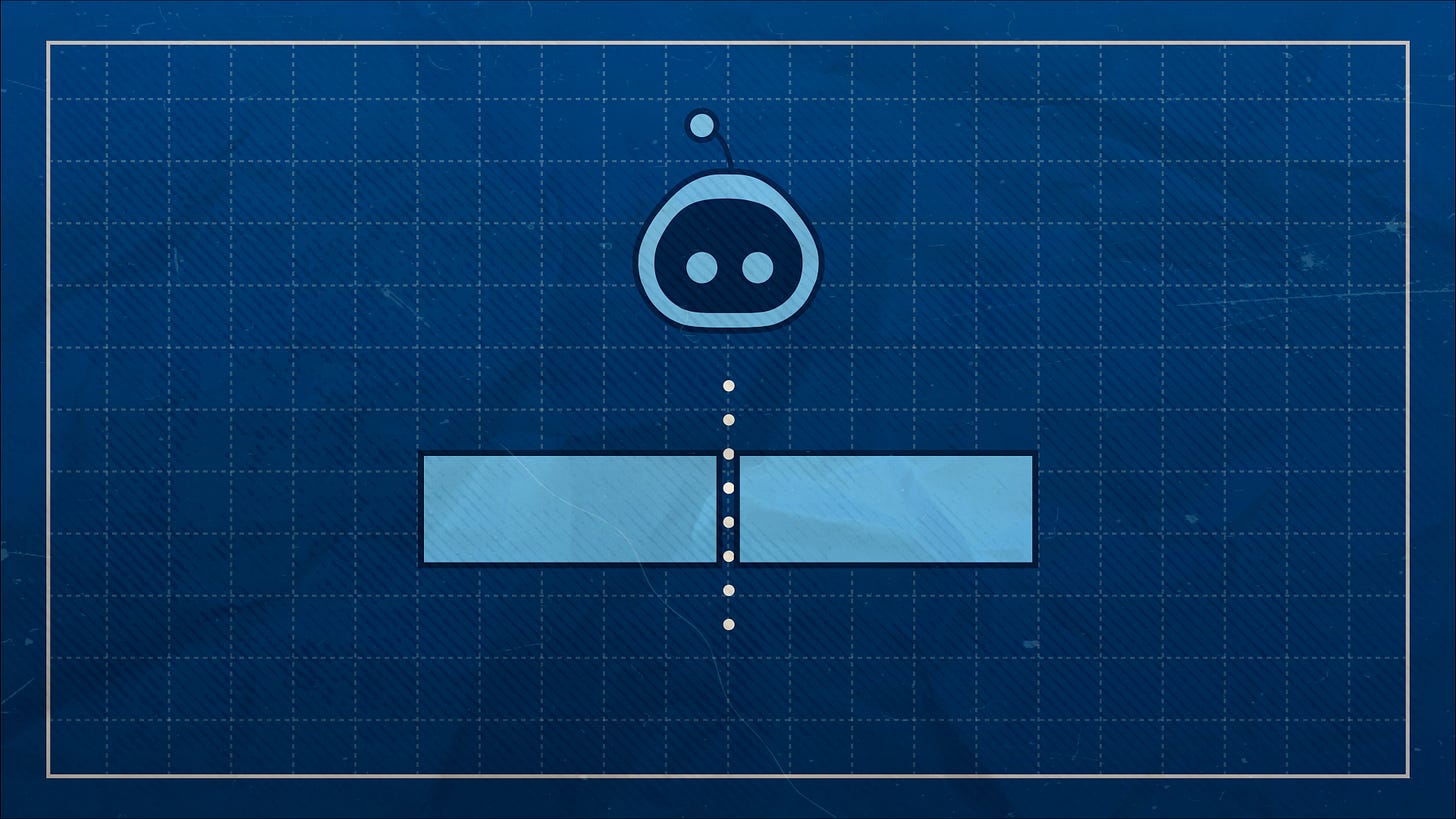

Here’s how it works. Every car in BeamNG is made up of a bunch of nodes. Just floating points in space. And then they’re held together with beams - which act like stiff springs that try not to stretch.

So when one of those nodes is moved by a collision, it will yank on all of the connected beams, which pull in all of their nodes - creating that realistic crumbled effect.

And so where most racing games just shaders and textures to represent damage in a purely visual way, soft body games like BeamBG and Wreckfest can literally squish and squash the model of the car to fundamentally change how the object moves, and interacts with the environment.

There’s so much more to BeamNG like aerodynamics and fuel consumption and so on - but most people just use it to recreate that one scene from Final Destination.

Far Cry 2

Okay. Let’s go to Far Cry 2. This game is famous for its fire propagation system. In this game a molotov cocktail can set fire to a patch of dry grass and it will spread into a raging inferno that will engulf nearby trees and buildings.

How does that work?

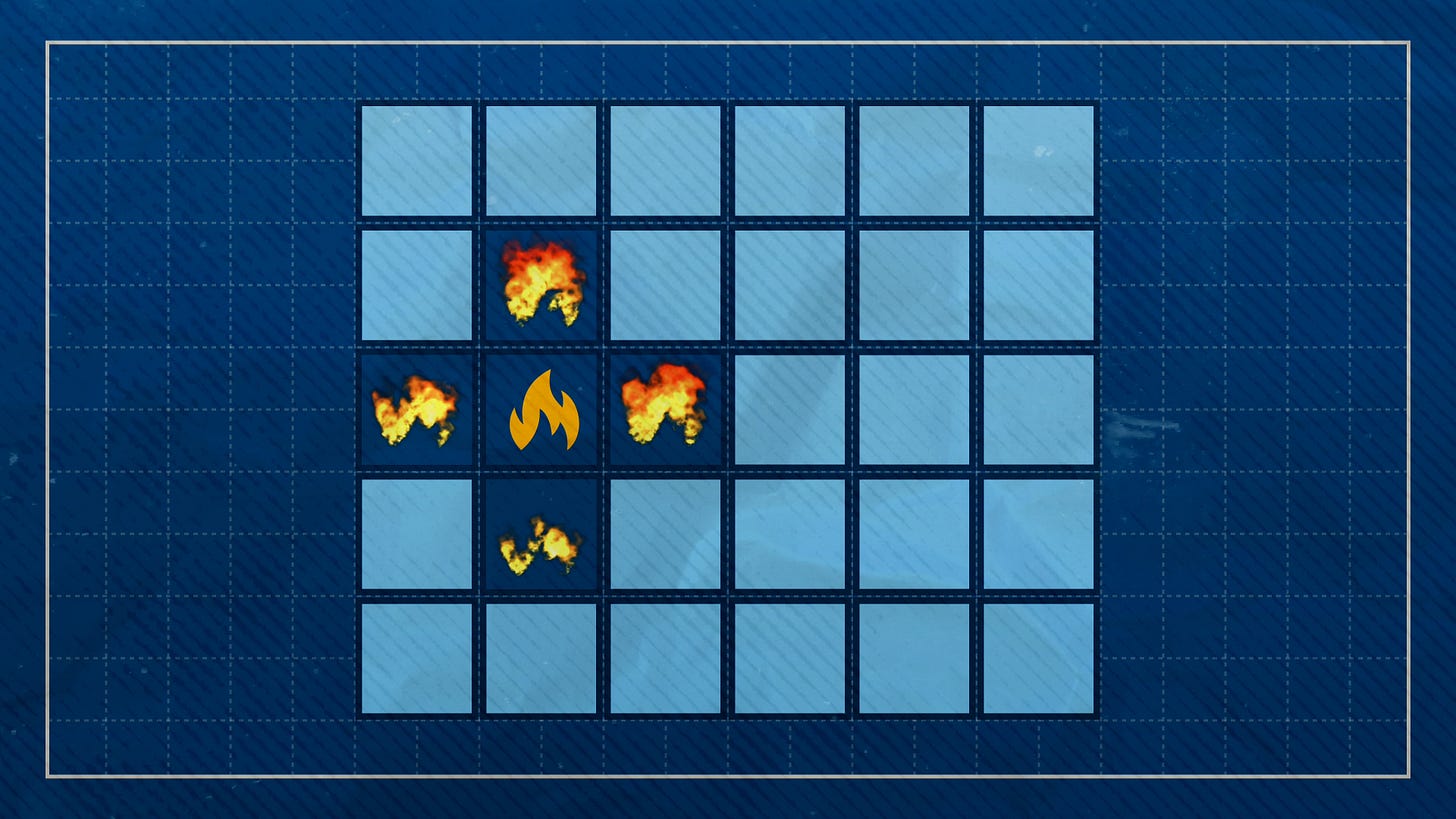

Well, basically, the game world is represented by an invisible grid that stretches over the floor. And each cell has a certain number of hit points. If the cell is flammable and loses all of its hit points - say, when you shoot a rocket at it - it will set on fire.

Then - a burning cell will start to damage its neighbouring cells. And when their HP reaches zero they’ll set on fire too, creating a chain reaction that will make the fire spread from zone to zone.

There are other bits of nuance to the system, of course. Each cell has a finite lifetime so it will eventually stop burning.

Different environments will have more or fewer hitpoints to represent, say, a dry patch of grass vs a wet jungle - the more hitpoints it has, the harder it is to set alight.

And burning cells will deal more damage to neighbours that are in the direction of the wind, to capture the effect of a fire being corralled by a strong gust.

it’s a deceptively simple system, but creates a really strong effect.

Teardown

Next up - Teardown.

But first, let’s start by looking at 2D games. So in a game like Spelunky, we can see that the world is divided into a grid of tiles. Then we create a simple destruction system by removing those tiles to create tunnels, pathways and chutes. The devs can just swap out the sprites of the neighbouring tiles to hide the rough edges.

And if you want more fidelity in your destruction, you can just reduce the size of the grid. In fact, you can go all the way down to destroying individual pixels as seen in Noita. In this game, every single pixel can be removed in order to dig through walls and floors with practically infinite granularity.

And so if we take that grid of tiles and extend it into an extra dimension we get... well, Minecraft. Minecraft is built out of cubes called “voxels”, which can be independently added and subtracted from the world to allow for completely free-form destruction.

And, in fact, lots of games use this voxel approach for destruction - including No Man’s Sky, 7 Days to Die, Astroneer, and the terrain smashing Donkey Kong: Bananza, where every layer is made up of hundreds of cubes that are packed together like dirt.

Most of these games use smoothing techniques and algorithms to avoid that super blocky Minecraft style in favour of something more naturalistic.

And then - like how we went from Spelunky to Noita by just reducing the size of the blocks, we can do the same in 3D to get a game like Teardown.

Teardown is basically Minecraft but with way higher resolution. Where Minecraft represents a piece of furniture as a single cube, Teardown represents it as hundreds or thousands of tiny blocks - all of which allows for much for precise destruction.

Though the other difference with the other voxel-based games is that Teardown has physics. There are no floating platforms here!

Basically, the game makes objects from a cluster of voxels. But if some of those voxels get loose from the cluster they are instantly turned into a new, rigidbody physics object - separate from the original. This means it can fall down, hit into other objects, and roll around.

Red Faction Guerilla

And then finally... it’s the reigning champion of video game destruction. Red Faction Guerilla.

This is a game where almost every structure on the Martian surface can be brought down with an explosive - or just a big swing of your trusty hammer. This is a game where buildings react realistically when you remove their foundations. And can even fall down and crush other structures in the process.

Now there are other games where you can destroy buildings. We just saw it in teardown. There are small structures in the Just Cause games that you can topple. And there’s fan favourite Battlefield: Bad Company 2.

In this game, buildings are made out of a large number of prefabricated pieces, each with two versions - an intact one, and a destroyed one. and when you do enough damage it will, you know the trick by now, swap the piece out for its destroyed variant.

So, that’s all cool, but all of these games struggle with a fundamental question: when does the building fall down?

Teardown does it when the object is completely detached from the ground - which means massive buildings can be held up by a single strand of voxels. And Bad Company does it after a certain number of those prefab pieces are destroyed - at which point it plays a pre-canned destroyed animation - but that all feels kinda arbitrary.

Ideally, we’d want to perform some kind of structural analysis to see if the building should stay standing, or whether it should fall. And that is exactly what Red Faction does - with a system that developer Volition calls “stress”.

Here’s how it works.

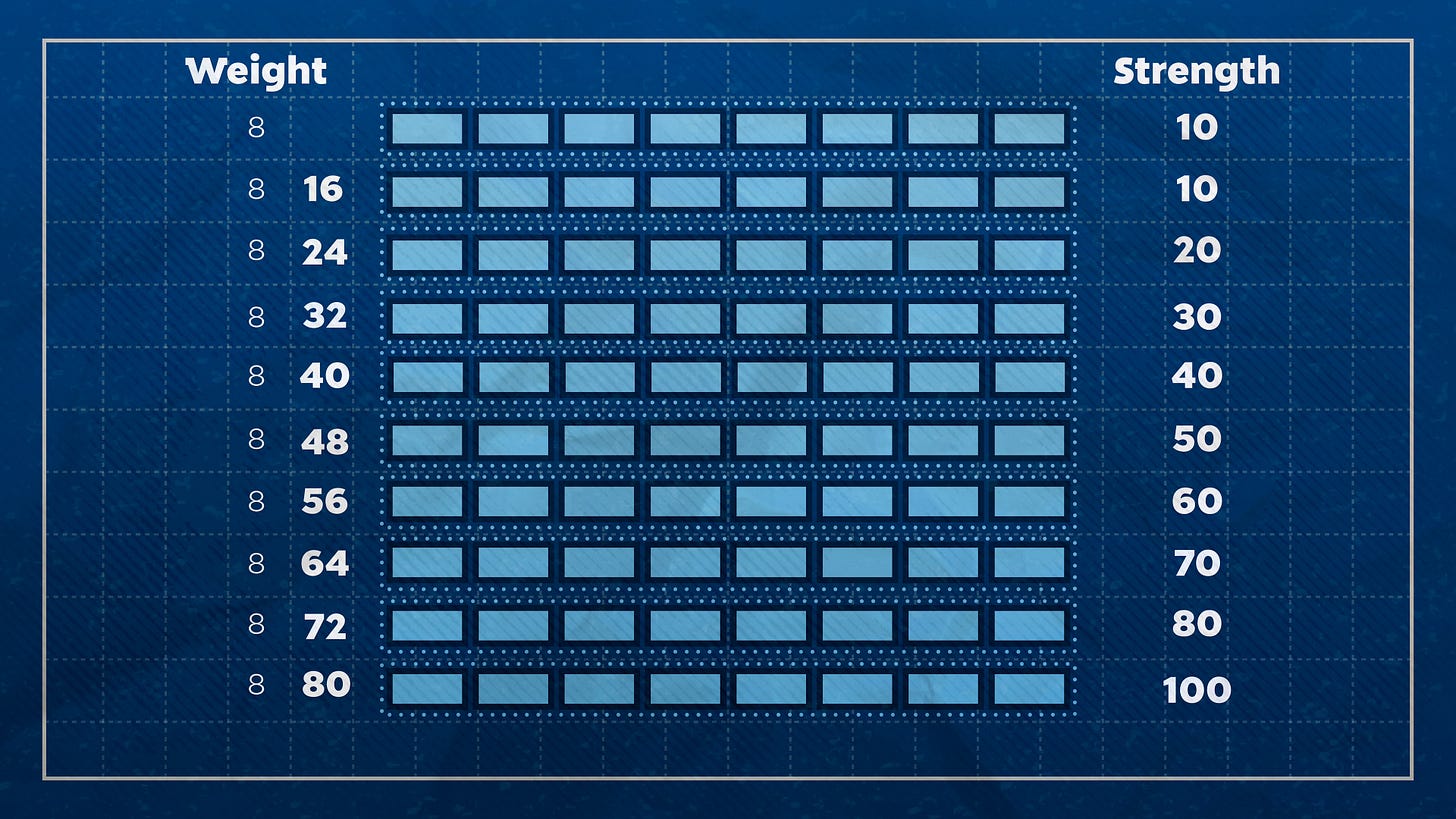

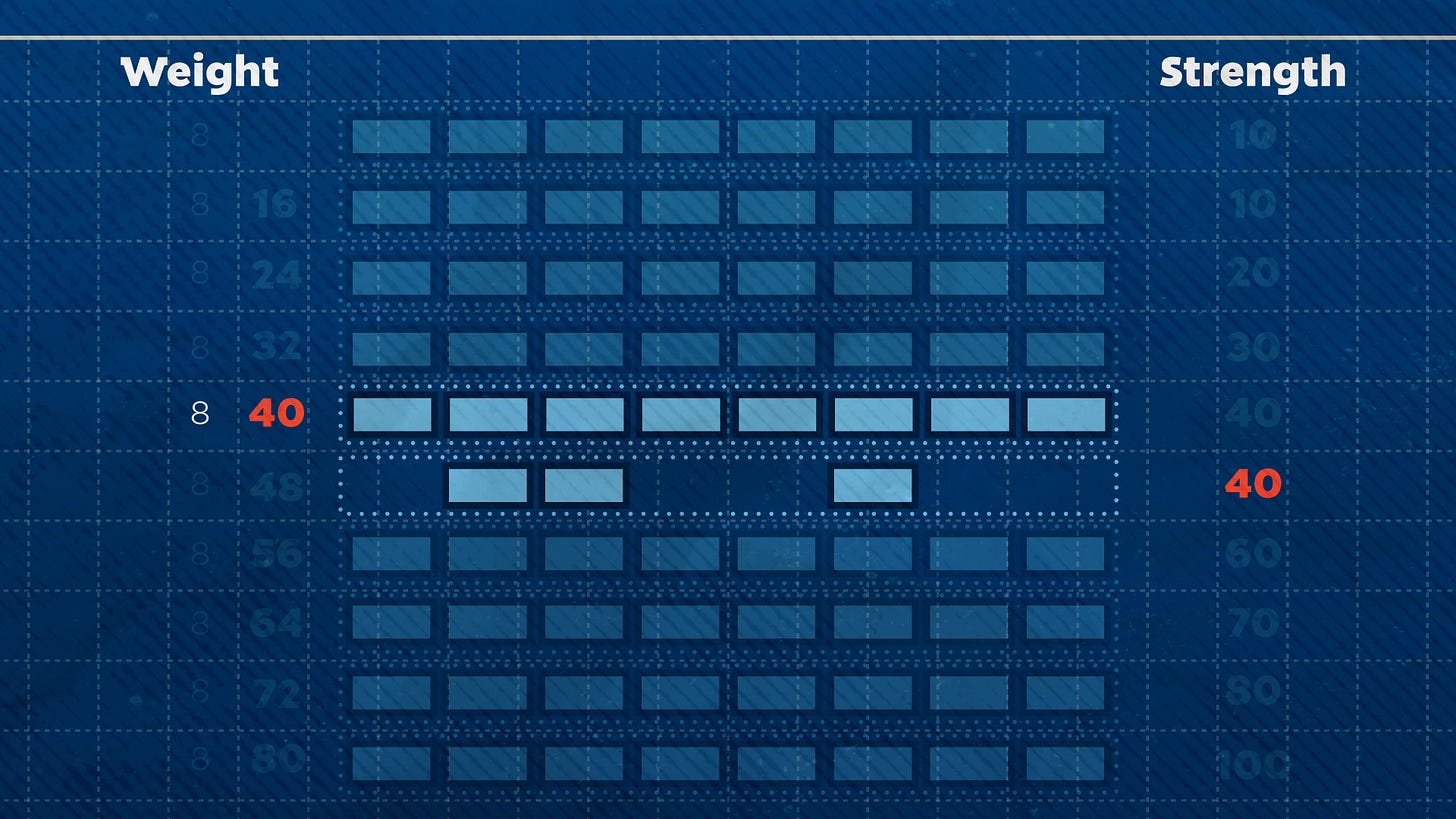

So, a building in Red Faction is made up of hundreds of individual parts that you can destroy. Let’s think of them like bricks. And then each brick has two stats. It’s force - which, for simplicity’s sake, let’s just think of it as how heavy that part is. And it’s strength - how much mass it can hold up.

We can then group all of the bricks into individual layers. For a simple building that will be a bunch of horizontal tiers like a big stack of pancakes. But it can be more complicated for horizontal structures like bridges and overhangs.

Then, we can tally up the stats on those bricks to get each layer’s combined weight and strength - keeping in mind that the weight must include everything above it.

And now we can do a stress calculation by simply asking - is the strength of one layer greater than the weight of the all the layers above it?

Now a building is designed, by Volition, to be architecturally sound and hold up its own weight. With different values for different materials - so a giant supporting concrete pillar has a much higher strength value than a pane of glass.

But, as we start destroying bricks we’re reducing the strength of that layer. And we can keep going until the strength is now less than the force of everything above it... at which point, the layer will fail and everything above it will turn into a bunch of physics objects that can come crashing down.

If you go frame by frame, you can see the exact moment where the upper layers change from static stuff to floppy physics bits.

And because those physics objects can inflict damage themselves, we can get into a situation where the top layer of the building will fall down and crush the layers beneath it. Or even fall to the side and make a big hole in the building next to it. Super satisfying.

Now there are plenty of limitations to this system. The game actually takes a while to actually do the stress calculation, which is why buildings sometimes take a while to fall down. But still - this technique allowed for an unmatched level of realism, detail, and player freedom... and that’s despite it being over a decade old, and running on a PlayStation 3. Which I think all goes to prove what I said at the start - that destruction is about ingenuity. It’s not a problem you can solve by just throwing more processing power at it.

....right?

Well, that is true. But what if we took Red Faction’s system and added the last 10 years of software and hardware advancements to it. Well then you’d get The Finals.

Yeah, this is a multiplayer arena shooter ala Overwatch, buy with truly absurd levels of destruction. Every building can be busted, blown up, bifurcated, and turned into bits. Over the course of a match the game world will crumble to pieces in reaction to rockets, mines, and explosive barrels. And it’s even possible to level the entire play space.

And the thing is - the system is basically identical to Red Faction. The developers were directly inspired by Volition’s work and so they used a very similar set-up. The buildings are made up of hundreds of fractured parts. The game calculates stress in real-time. And if a layer’s force exceeds its strength, then the whole thing comes down.

Except... it’s now running on Unreal Engine 5, with Nvidia PhysX, and the min spec asks for 20 times more memory than you’d find in an Xbox 360.

Conclusion

So those are some of the most effective techniques used for adding destruction to games. Swapping props. Splitting the world into breakable cubes. And performing quick stress tests on buildings. All of which can make for an impressive imitation of real-world demolition.

And now you know the tricks - you might be wondering why we don’t see this level of deformation in every game.

And I think it’s because, well, each one of these techniques has some big knock-on effects for the rest of the game. Not just for performance and memory - but also stuff like lighting, sound, and AI pathfinding - all of which must be able to adapt to a world that’s constantly changing and moving.

And then - on top of all of that - there’s game design.

Teardown designer Dennis Gustafsson says “the idea of a fully destructible environment is compelling for the player but a nightmare for the game designer”. And Noita maker Nolla says “It’s easy to think that having a complex or highly realistic simulation will auto-magically result in interesting gameplay. Often, that’s not the case”.

And that’s because, well, game design is usually about setting limits and restrictions, about rules and constraints. and destruction can throw all of that out of the window.

Donkey Kong director Kazuya Takahashi says “In most games, level design is a bit like designing a course. You’ve got a main route you want players to follow, and you build paths to guide them along it. But in this game, even those paths can be destroyed. If you instead dig a tunnel and sneak around to grab [a Banandium gem] from behind, that’s equally viable. Designing levels with that kind of flexibility in mind was a huge challenge”.

So it’s like anything else that can be added to a game - it must be done for a reason.

Perhaps it’s for new combat gameplay, like denying enemy cover, creating new lines of sight, or collapsing structures on enemies. Maybe it’s to let players be crafty by making tunnels, trapdoors, and slides. Perhaps it’s for creativity, or immersion, or replayability, or a deeper sense of simulation.

Whatever the case, and however you implement it - destruction should be there to support your game design goals, not blow them to bits.

I’m Mark Brown, thanks for reading.