In The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, Links newest tool isn’t a weapon, or a musical instrument, or a shape-shifting mask.

Instead, it's a magic arm that lets you whip objects around in mid-air and then stick them together with big wodges of glue.

The Ultrahand - named after one of Nintendo's mechanical toys from the 1960s - lets you make vehicles, aircraft, platforms, structural supports, puzzle-solving tools and - if you've got a lot of patience - giant mechanised robots and nuclear-powered war machines.

But how did Nintendo design such a madcap game mechanic - without the whole thing falling apart? Well, I scoured every single interview that the studio has given on this game to find out the in-depth details.

I'm Mark Brown and this is how Nintendo made Ultrahand.

So, shortly after finishing Breath of the Wild's downloadable content, director Hidemaro Fujibayashi started thinking of ideas for the next Zelda game. And he came up with the idea of letting Link build his own contraptions, like a pointy-eared MacGyver.

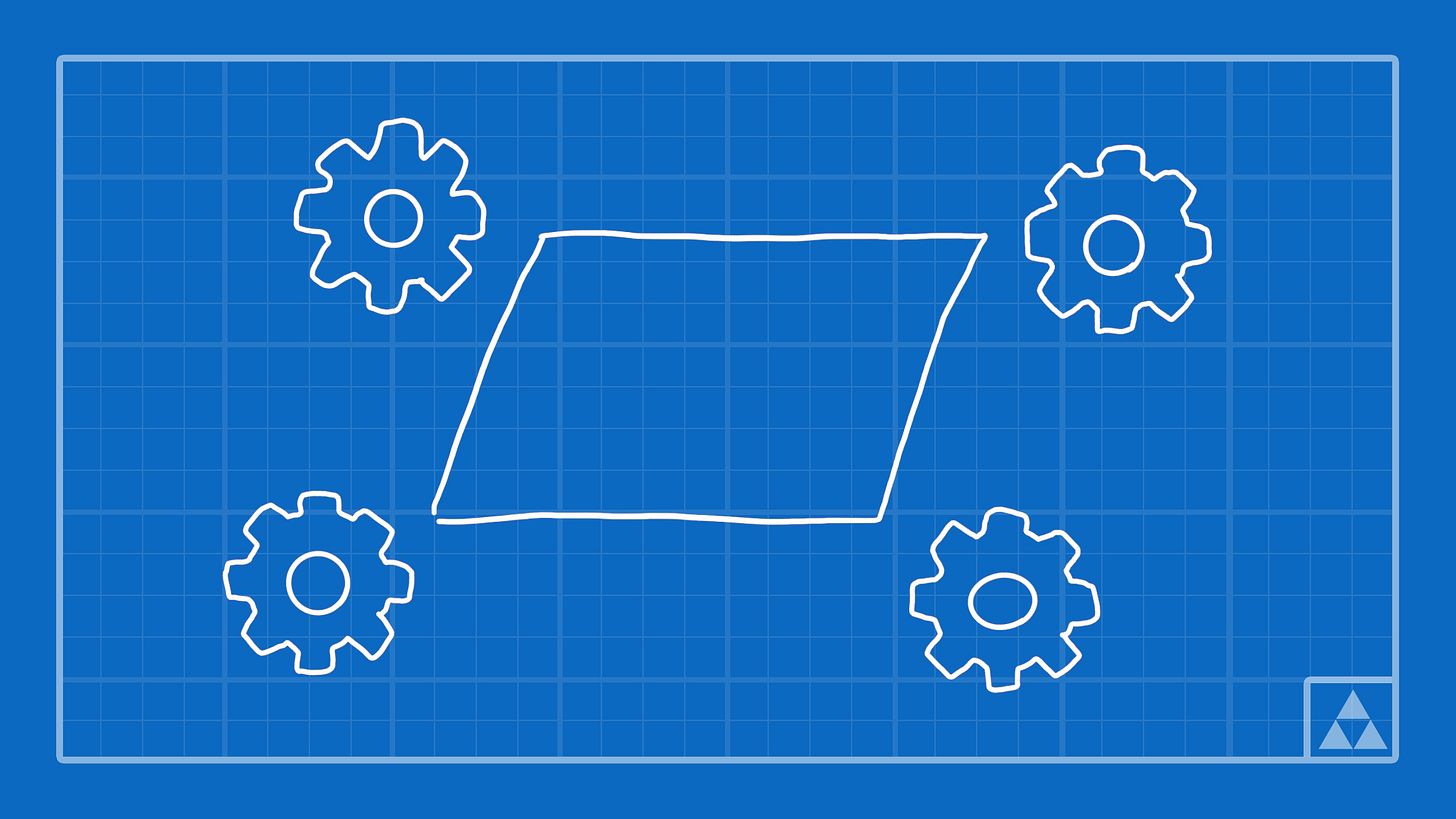

Now, Nintendo designers are encouraged to create playable prototypes before pitching new game ideas. So Fujibayashi built a demo using the Breath of the Wild engine.

That game has dungeons with these perpetually spinning cogs - so the director took four of them and attached them to a stone slab to create a makeshift car.

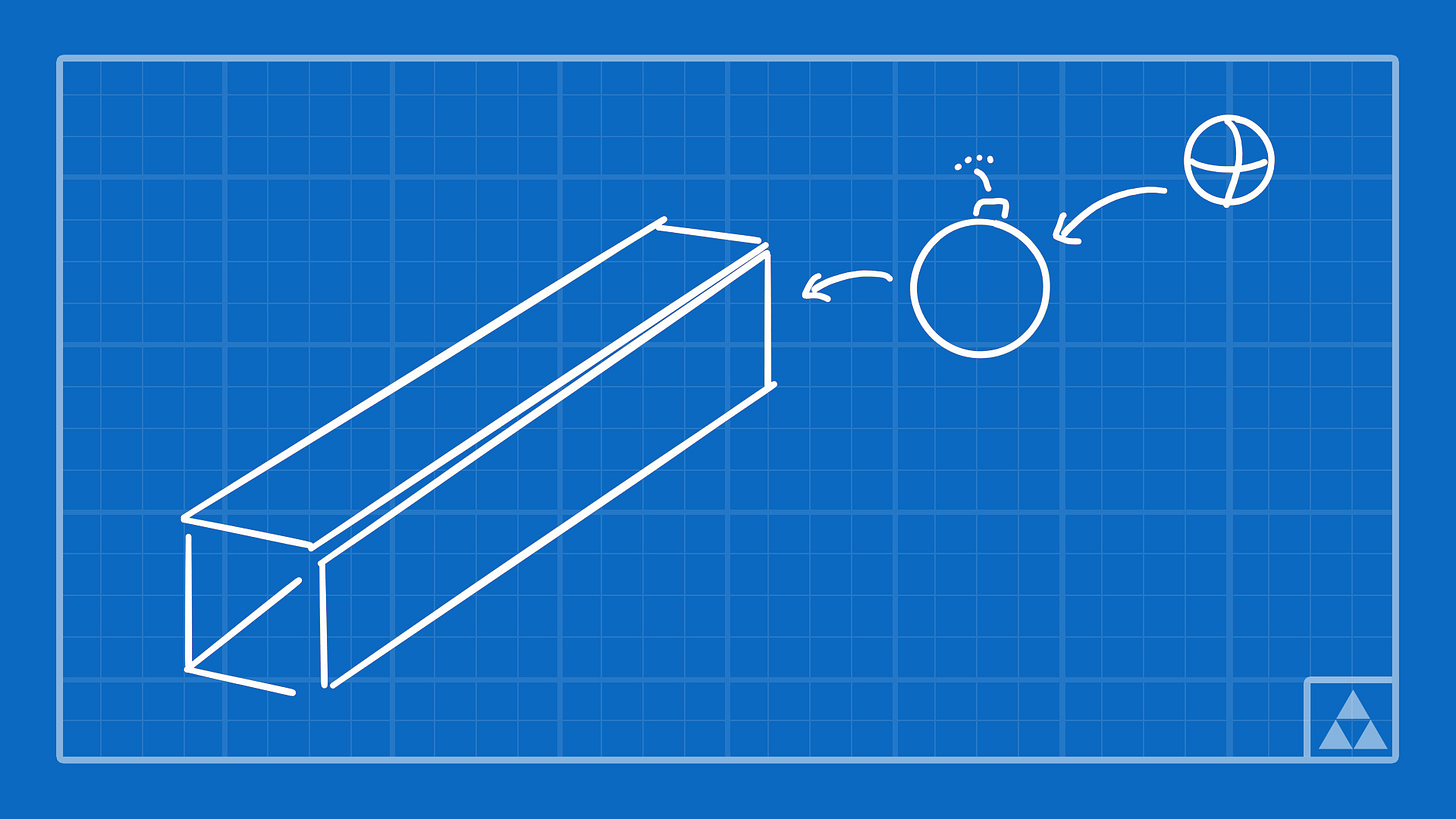

Then he put four long slates together to make a tube - and if you place a bomb and a ball in the tube, you get a cannon. Put it together and you've got a DIY tank, rolling through the fields of Hyrule.

If he had any doubt that the gameplay would appeal to fans of the first game, Fujibayashi could just look to YouTube, and other platforms, to find players already using the limited tools provided by Breath of the Wild to make vehicles and machines.

These videos, and Fujibayashi's demo, gave Nintendo the confidence to make the mechanic and the proposal was quickly approved by Zelda bosses Eiji Aonuma and Shigeru Miyamoto.

Simplicity

Now Nintendo's primary goal when developing Ultrahand was to keep things simple. It should always feel like making stuff in Lego or Minecraft, rather than trying to learn how to use Blender.

Because if this thing was complex to learn or fiddly to use, it would overwhelm new players and frustrate those who didn't really want to engage with the feature any more than they had to.

“We wanted to make sure that the system itself is simple enough that anybody can pick it up and play without too much issue. The more we weed out complexity upfront, the more versatility and freedom there is to provide options [later]”

Hidemaro Fujibayashi, Nintendo

So the mechanic went through endless iterations with the goal of making it more streamlined. If it initially took five steps to build a basic raft, the designers would rethink every part of the building process until players could put together a boat in just one or two actions.

This simplification came in various forms.

For instance, the game initially allowed you to rotate objects in tiny one degree increments so you could make fine-tuned adjustments to your build. But the final game moves in chunky 45 degree rotations to get things done faster.

And by having objects snap together at predetermined points, the tool makes it quick to set up things like wheels, and steering points.

It's also just very playful. Building takes place in the world, rather than a separate menu. And objects topple and crash into the floor as you move them about. And there are tactile controls, like wiggling the stick or joycon to break your creation apart. If you enjoy using something, it's always easier to experiment and learn.

Another source of simplification was the Zonai devices. These are special tools that add powerful capabilities to your build like fans, wheels, cannons, and floating platforms. Nintendo came up with dozens of ideas for these things but pared the list down to just the bare minimum so as to avoid decision paralysis.

Plus, while Nintendo experimented with having a separate switch item to turn the Zonai devices on, they simplified things to the point where you just hit any part of the machine with a weapon to simultaneously switch on all of the connected devices.

(As a nice side effect, this elegantly affords a way to activate your machinery from a distance, using arrows).

It was also just as important to consider the way these devices look. Instead of using supernatural objects, Zonai devices are meant to resemble real-world objects and home appliances, like a desk fan, a skateboard, a fire hydrant, and a light bulb. Even the stabiliser should be familiar: it's modelled after those toys that always right themselves, like Japanese Daruma dolls or, you know, Weebles. That wobble. But don't fall down!

“If players are shown something they've never seen in real life, they'll have no idea how to use it. But if it looks similar to an everyday item, they'll understand how it should be used intuitively”

Eiji Aonuma, Nintendo

And this principle is seen everywhere in the design of the Ultrahand and its related mechanics.

Machines are powered by big batteries, rather than some vague magical source. Zonai devices come from giant gashapon machines - which is a clever way to explain that you're about to get a random selection of tools. And objects that can't be moved are intentionally tied down with rope or cloth.

And then there's the glue that seeps out from between different objects. Aonouma initially wasn't a fan - as a wood carver who works hard to hide the connections, he thought the visible glue was ugly. But he soon came to see that it was an obvious visual clue that two objects are attached.

Feelings

Now, simplicity wasn't the only goal for Nintendo when making Ultrahand. The team also carefully focused on the feelings that such a tool could engender in its players.

That includes, of course, creativity. Fujibayashi knew the mechanic would be a hit when staff members were excitedly sharing videos of their creations while playtesting. And despite the streamlined design and limited number of Zonai devices, players have still managed to create absurdly impressive machines. Stuff that even surprises Nintendo.

Another feeling is humour. Nintendo is well aware that the Ultrahand mechanic is prone to problems - like accidentally activating a machine and having it run away from you, or watching your beautiful new tank go up in flames because you made the whole thing from wood. Ya doofus.

But as long as players find those failures funny, the mechanic is working fine. We also see this in two often-repeated side quests: transporting Koroks and helping out Addison with his lop-sided signs. Both of which lend themselves to all sorts of slapstick silliness.

But perhaps the most important feeling is one of agency.

Breath of the Wild already gave players lots of tools to come up with their own solutions to problems. Aonuma observed that people were taking "pride in the things they accomplished and finding their own playstyle".

But with Ultrahand, the options are endless. Where the last game let you climb up any mountain, this one lets you fly up to the summit in seconds with a custom-made goblin glider.

And for Nintendo, this meant ceding the power it holds over players. While classic Zelda games typically have puzzles with a single, specific, designer-made answer to figure out, Tears instead provides open-ended problems that can be completed in any number of ways. Nintendo just hands out the tools and leaves players to find their own solution.

We've placed more importance on creating a game that enables players to do exactly what they think they can do, rather than how we want them to play the game.

Takuhiro Dohta, Nintendo

Even if... that means cheating. Many obstacles in Tears of the Kingdom can be overcome by using the Ultrahand - and Link's other powers like Fuse, Recall, and Ascend - in cheeky, unanticipated ways.

It's all part of Nintendo's plan, though: a clumsy cheat is still fun because the player feels like they're the only person in the world to have figured out such a mischievous solution. Better than finding the exact same answer as everyone else.

Though, this still needed some amount of balance. Internally, testers quickly figured out ways to make perpetual motion machines that could move across the map with infinite power. That stuff had to be nerfed to make the game work at all.

Fujibayashi and co spent a long time finding limits would that would allow players to really get creative, but at the same time make sure the game still worked as a game.

So Ultrahand is a really fun tool that allows for creativity, slapstick humour, and an alarming amount of player agency. But Nintendo had to spend years making it work the way it does in the final game - with endless iterations to the tech to make it simple to use. And also, somehow, not a complete buggy mess.

Wizards.

Nintendo employs wizards.

It's the only explanation.