Super Mario's Invisible Difficulty Settings

Easy, medium, or hard?

Nintendo has been trying to solve the exact same problem, for the last 30-odd years: how do you design the difficulty of a Mario game?

Because here’s the thing: Mario means different things to different people.

On the one hand, he’s a cultural icon, a Hollywood super star, a pudgy plumber mascot for kids. And so his games must be approachable to absolutely everyone - even to someone who has never played a video game before.

But on the other hand, Mario has gathered a rabid fanbase of gamers who have been playing his adventures since 1985 and now have expert, muscle memory skills for triple jumps, ground pounds, and infinite 1-UP shenanigans. And so they expect Mario’s games to keep pace with their advanced skillset.

How on earth do you make a game that’s suitable for both of those players - and everyone in between?

“No matter how hard you try,” says Mario’s creator Shigeru Miyamoto, “it just isn't possible to settle on a difficulty level that will satisfy everyone”.

Now, in another genre this might be fixed with a difficulty select screen. You know… do you want to play on easy, medium, or hard? But these features are usually created by tweaking some numbers, like the amount of health you have, the damage you do with each attack, or the number of enemies that spawn.

But in a meticulously hand-crafted platformer, with extremely distinct interactions between enemies and the player… well that stuff just wouldn’t fly.

Which is why, in more than 30 mainline Super Mario games, only one has anything even resembling an explicit “easy mode”. And besides: that’s just not really Nintendo’s way. Miyamoto says ”one way is to add an “Easy Mode”, but I think the best method is when the player can adjust the difficulty [themselves] while playing”.

So how does that work? Well, that’s what I wanted to find out.

I played a bunch of Mario games. Okay, a lot of Mario games. Okay, fine - I played every single mainline Mario game. All in order to find out how Nintendo designed Mario’s invisible difficulty settings.

Okay. So I think the best metaphor for Mario’s difficulty design is to think of three pipes, placed on top of each other.

The central pipe represents the path you must take to finish the game. To go from A to B. In a level, that’s from the starting line to the goal pole. And in terms of the game itself, it’s from the opening cutscene to the final showdown with Bowser. This is the critical path - and it’s designed to be a pretty average level of difficulty.

But then there’s the other two pipes - in the lower pipe the game is easier and more forgiving for new players. And in the pipe up above, the game is harder, and designed to test the skills of expert players.

And then within the game’s design there are ways to shift between these three pipes. If the game is proving too difficult, you can accept some help and drop into the bottom pipe and have an easier time. But if the game is a little too easy, you can rise to the top pipe and take on the game’s more challenging content.

Now this is an idea that Nintendo has used in, well, just about every Mario game. From World to Wonder, and from Galaxy to Odyssey. But the exact ways that players can move between the pipes has changed a lot throughout the years.

We’ve seen these methods evolve and change as Mario has bounced between different systems, eras, game directors, and meta-level structures. So let’s look at them all - by breaking them down into different categories.

Upping the difficulty

I’ll start by looking at the top pipe, with the stuff that allows the player to make the game more difficult. And that starts in the levels themselves, with one-off rewards that encourage you to take risks.

For instance, there’s a block in the first underground level of Super Mario Bros. When Mario bops it with his bonce, a 1-UP mushroom appears and starts to saunter across the ceiling. If you want it then you’ll need to speed up, manically dash through the next group of enemies, and make a daring leap to grab the extra life before it disappears into the void.

Mario levels are absolutely filled with this stuff. Whether that’s runaway power-ups, those coloured coins that disappear after a few seconds, or the final tricky leap to the top of the flagpole. These are all entirely optional, meaning that if you’re not confident then you can just ignore them entirely. But if you’re feeling skilful then you can push your luck, and get a reward for it.

This is never more obvious than the star coins, which were formally introduced in New Super Mario Bros. on DS. Every level has three special coins which require extra skill - or even more advanced moves. A Nintendo designer said “all of the courses can be cleared without dashing or wall jumping, but you can't get Star Coins without doing those things or making use of special items.”

These star coins have become a recurring motif and now show up in just about every Mario game - perhaps in a slightly different guise, like the green stars and Miiverse stamps in 3d World, or the comet medals in Galaxy 2.

Again: these things are entirely optional and - in many games - you can finish the game without picking up a single one. But, to an advanced player, they transform an easy level into a challenging obstacle course where you have to risk life and limb to walk away with all three coins.

Another idea is to reward the player if they can finish a course under specific criteria.

Yoshi’s Island is one of the easiest Mario games thanks to a very generous regenerating health system that lets you take, well, infinite hits. So it’s entirely possible to limp through a level in the most ungainly way imaginable. But - the game will score your performance at the end of the stage, and one of the criteria is how much life you have left when you cross the finish line. So if you want to max out the score card you’ll need to finish the level with almost perfect performance.

Score has always been part of the Mario games, of course - a weird relic of its arcade roots. But Super Mario Bros. Deluxe gives each level a par score to hit, as an optional challenge - which is a more concrete goal than simply “get a lot of points”, or “beat your friends”. And in Super Mario Maker’s 3DS port, every level comes with two medals which add special conditions to the stage - like fishing it while holding on to a certain power-up, or speed-running through a level under a super strict time limit.

So those are ways to place optional challenges within the levels themselves. but what about if we zoom out and think of the game as a whole?

In Super Mario Odyssey you can finish the game after collecting 124 power moons. This unlocks the climactic final battle with Bowser on the moon - which wraps up the story. Roll credits. The game is over.

Except, of course, it’s not. Doing this unlocks access to new moons which are now scattered throughout the game. And tricky additional post-game levels that will put everything you’ve learned to the test. Basically: the most difficult content in Mario Odyssey doesn’t even exist until after you’ve finished the game.

So if we think about the game’s difficulty curve, Nintendo could have forced players to reach the very end before offering closure. But instead, they stop the story long before the curve hits its peek. This means that pretty much everyone can see the game through to the end, and wrap up whatever little storyline there is in the game. But those wanting more challenge can keep on playing.

This is a common refrain in the Mario series - heck, the very first Super Mario Bros. ended with an invitation to start a new quest, which is like a B-side remix of the entire game with harder enemies and level layouts.

Plus, if you find all 120 stars in Mario Galaxy, you’re rewarded with the chance to do it all again as Luigi. Finishing Super Mario 3D World unlocks three more worlds filled with difficult courses - and the infamous Champion’s Road. And all of the New Super Mario Bros. games have bonus worlds with more difficult courses, hidden after the credits roll.

Of course, this does mean that expert players have to go through an entire game’s worth of pretty easy content to finally get to the challenging stuff. So other games don’t make you wait until the very end to access these bonus harder levels.

In Super Mario World, certain levels have secret exits that open hidden pathways on the map - some of which go to a mysterious place called Star Road, which hides a bunch of bonus levels that will test your mettle. There’s even a secret world within this secret world: a Special Zone, filled with bizarre dream logic levels with the most 90s names imaginable. “Tubular”! “Groovy”! “Way Cool”!

Other examples include the challenge mode in New Super Mario Bros. U, which is unlocked gradually as you play the game. And the odd extra difficult courses that are peppered throughout Mario Wonder’s campaign.

But how about we go one further, and make the entire game be designed just for those who were experts at the first one?

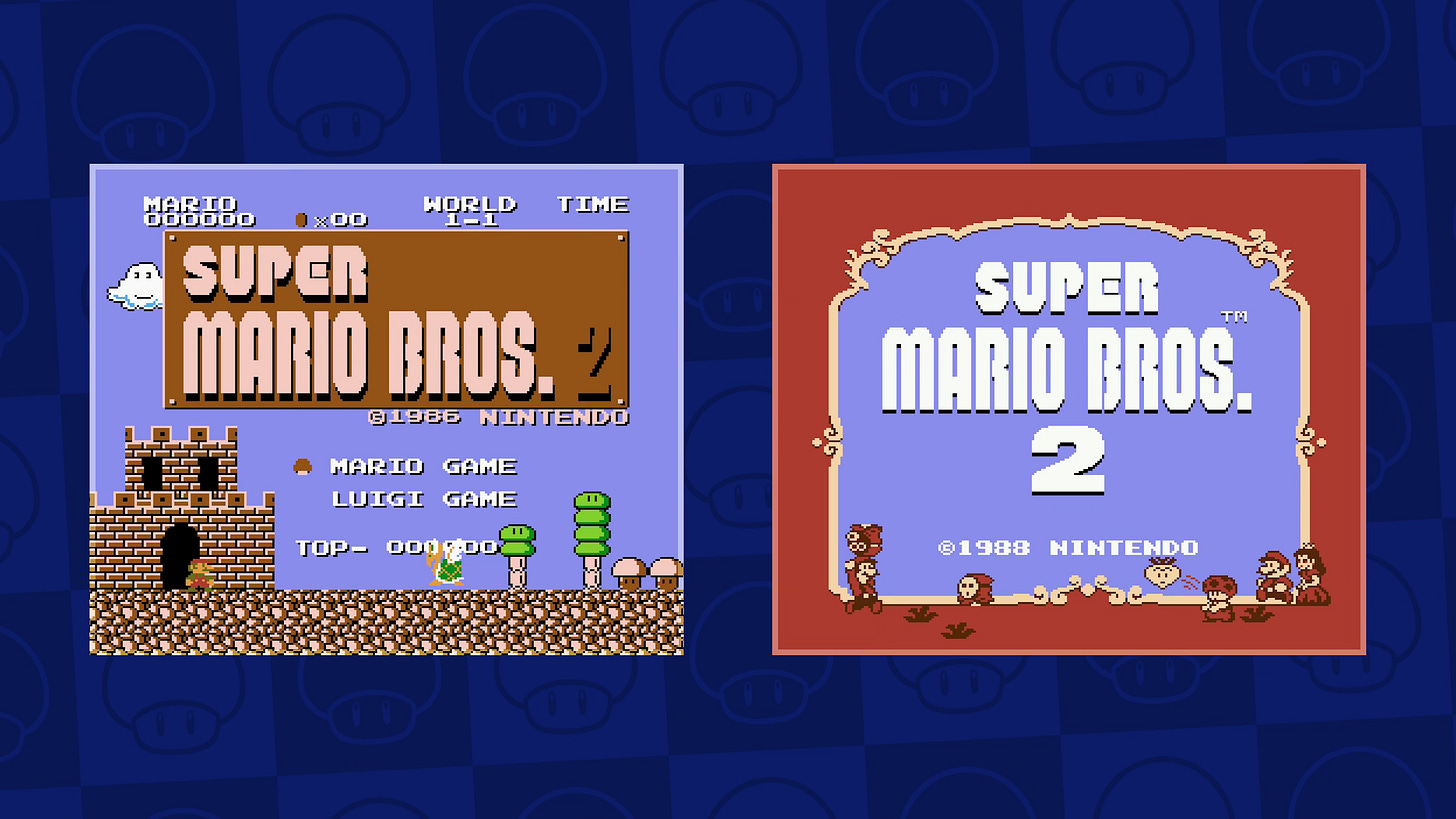

Shortly after the release of the original Super Mario Bros., the designers put together a sequel that was full of extra challenging stages - with nonsense jumps, BS enemy placements, absurd wind physics, poisonous mushrooms, and warp pipes that can send you backwards to earlier worlds.

The entire game is a nightmare joke for Mario experts - so much so that it was hard to market it properly. Miyamoto has said [1] “we were certain that this was a lot of fun for those who played Super Mario Bros. immensely. But we thought it would be hard for first time players, so we put a sticker on the package that said ‘For Super Players’.”

That wasn’t enough for Nintendo of America who refused to localise the game - which is why we got a completely different Super Mario Bros. 2 outside of Japan.

Anyway - this idea makes a lot more sense in the age of downloadable content. So, if the old eShop still existed then you could grab some stupidly hard levels for New Super Mario Bros. 2. Or, even better, the excellent New Super Luigi U expansion pack, which is designed for platforming experts thanks to its tricky stage layouts and super short time limits.

So, those are all ways that Nintendo can make Mario games more challenging.

Risky one-off rewards.

Optional star coins.

Challenging bonus criteria.

Post-game content.

Bonus levels.

Expert-level DLC.

But what about the opposite? What can Nintendo do if the central pipe is proving too difficult and players need a helping hand?

Giving a helping hand

Well, one very effective solution is to simply let players choose which courses they take on. Super Mario 64 features 120 power stars, littered throughout a number of difficult levels - but you actually only need 70 of them to finish the game.

This means that outside of a few mandatory stages, the player is able to pick and choose the levels they feel comfortable playing - and skip others entirely. And because you can access multiple levels simultaneously you can put off a tricky level for the time being and come back to it later.

This has become a common structure in Mario’s 3D outings - you never need all of the stars, shines, or moons to finish these games, and so you get to decide which levels you want to play, and the order you want to play them in.

But we also see the option to skip levels in some 2D games - whether that’s using the warp zones in Super Mario Bros. to skip past tricky worlds, using the map screen in Super Mario Bros. 3 to bypass courses, or using the job list in Super Mario Maker 2 to pick out the levels with the lowest difficulty ratings.

Another solution is to change the layout of the levels themselves. In Super Mario World there are these switch block palaces. Hit the big coloured button and it will populate the world with new blocks that fill in tricky gaps or provide useful power-ups. This makes levels much easier to play - which is a bit like activating an easy mode.

Though, because you can’t undo the action… this doesn’t really let you move back and forth between the pipes. Press the button and you’re now stuck in the lower pipe for the rest of the game.

Luckily, this idea would be revisited more effectively in Super Mario Wonder with a badge that makes some extra blocks appear. But only as long as you’re wearing the badge. Take it off and the game goes back to normal.

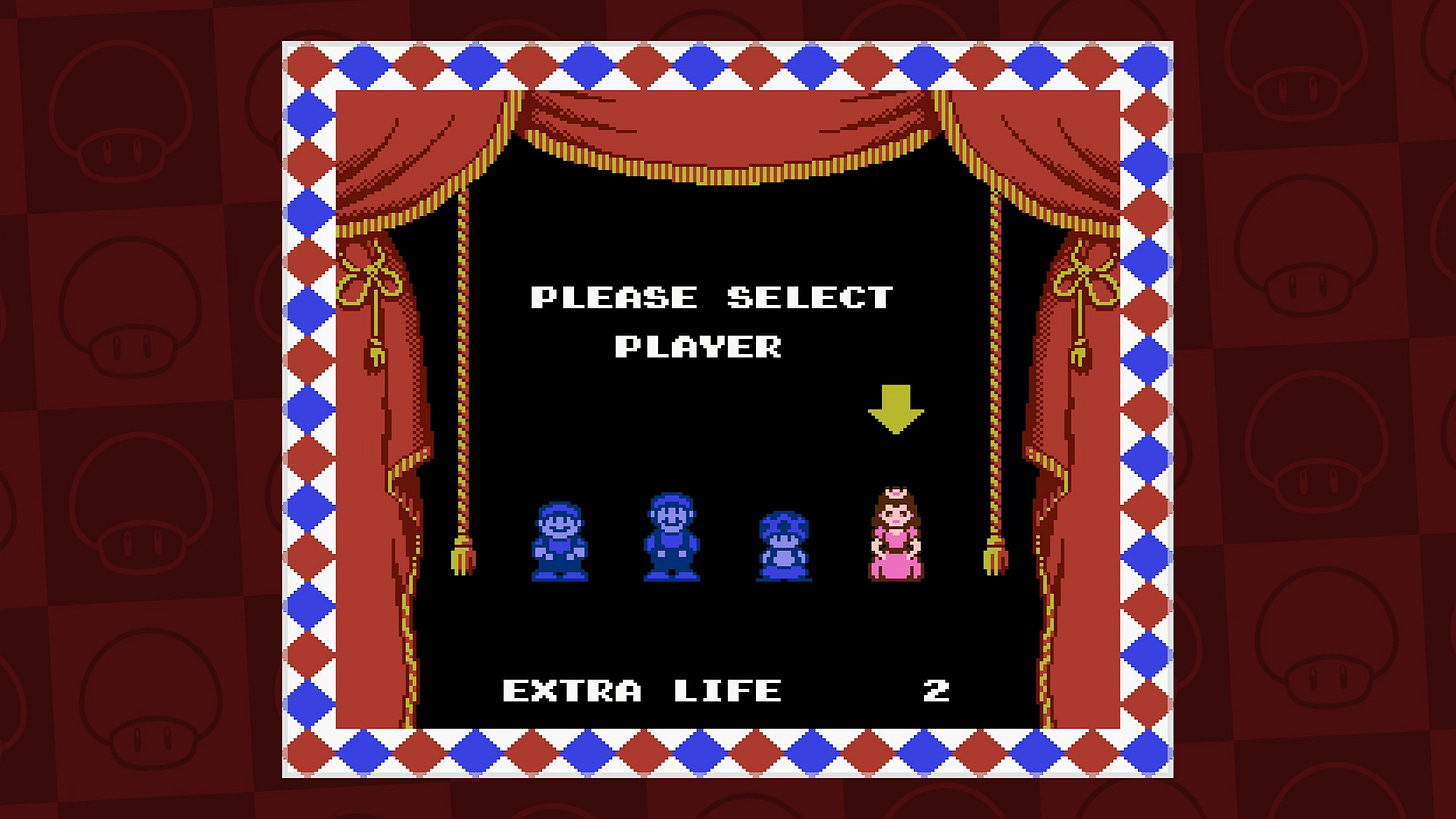

Nintendo can also change the difficulty by letting you switch to a different character. In the western version of Super Mario Bros. 2, Princess Toadstool is arguably the easiest character to control thanks to her floaty jump that makes it less challenging to land on small platforms. Same goes for her appearance in Super Mario 3D World.

This is taken even further in New Super Mario Bros. U Deluxe, where Toadette and Nabbit are dedicated as easier characters to play as, thanks to tighter physics, faster movement in water, and - in Nabbit’s case - the dude doesn’t even take damage from enemies. Changing the difficulty is as easy as changing character.

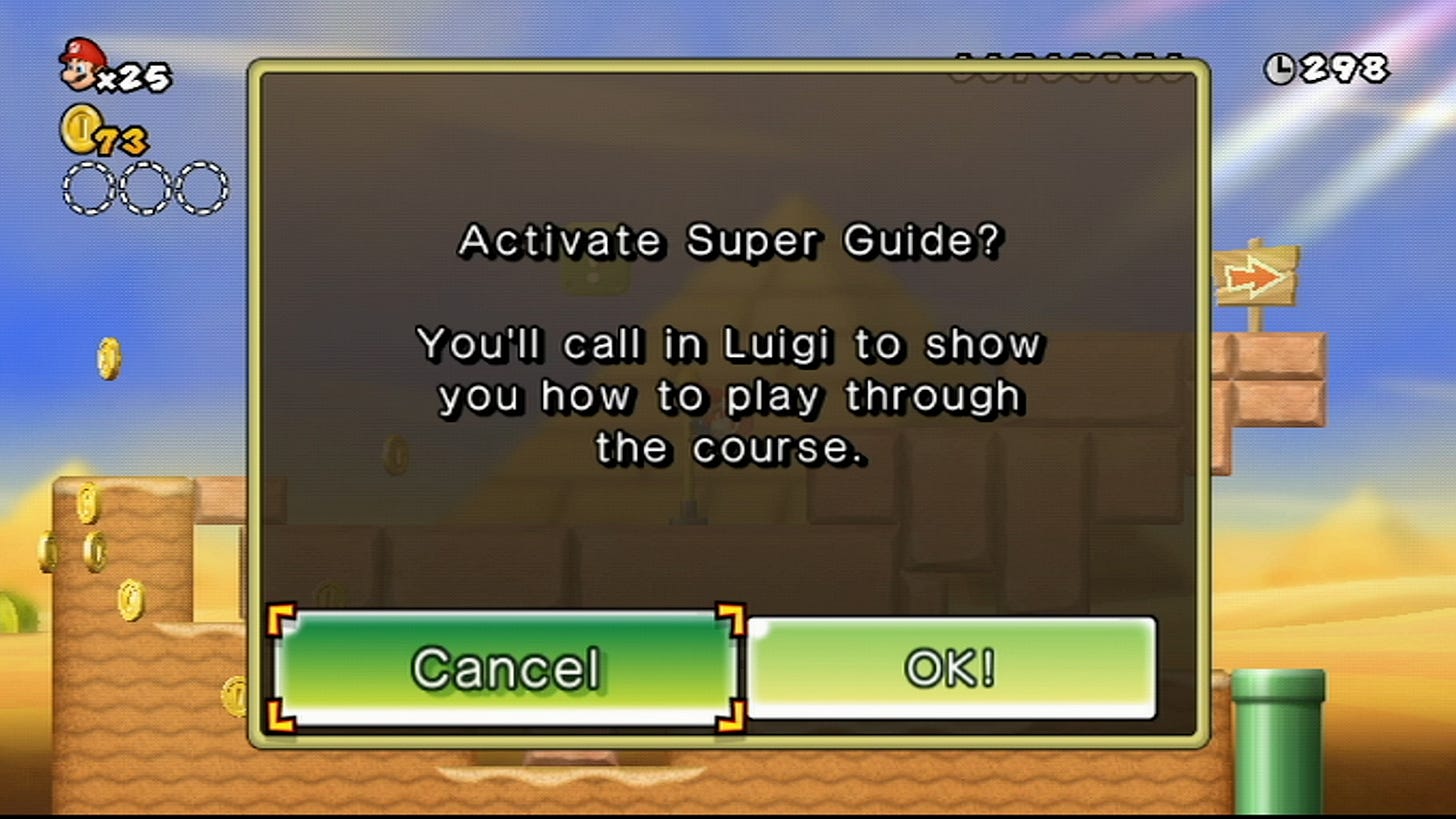

In New Super Mario Bros. Wii, Nintendo wanted to do something for players who kept dying, over and over again, on the same level. These players are obviously getting stuck and probably quite frustrated - so how can they be helped? The solution is the Super Guide.

Activate this box and Luigi will show you how to finish the level - notably, without getting secrets or star coins. When he’s done you can either take the, uh, take the L and skip the level. Or use what you just saw to try the level again for yourself.

This feature would appear again in New Super Mario Bros. U, and in certain parts of Mario Galaxy 2 as the slightly unsettling Cosmic Spirit.

You could perhaps put the assist mode for Mario Odyssey in this category too, as one of the primary features of this system is to show you exactly where to go using these handy blue arrows.

A slightly different version of this system appeared in Super Mario 3D Land. You’ll still get an optional box if you fail a certain number of times - but in this game it provides a power-up: an invincible tanooki suit which lets you float forever and smash through enemies and obstacles. If that’s not enough, then dying 10 times lets you skip the level altogether.

The invincible tanooki suit is actually a callback to a power-up in Super Mario Bros. 3. Finishing a castle can sometimes net you a P-Wing for your inventory, which can be used to give you infinite flight and soar over an entire level like you’ve activated a broken Game Genie code. A similar assist system appears in New Super Mario Bros. 2, and there’s a clever twist on the idea in Super Mario Maker 2’s story mode where you can open a toolbox of items and blocks to paint into the level as you see fit.

And finally… if you’re stuck in a game, sometimes the best solution is to ask a friend to jump in and just do it for you. But what if they could actually play alongside you and help out. That was the idea behind Super Mario Galaxy’s co-star mode, where a second Wii Remote can be used to collect and shoot star bits. In Galaxy 2, the second player can even kill enemies.

There’s also a particularly clever version of this in New Super Mario Bros. U, where a second player can plop temporary blocks into the world by tapping on the Wii U gamepad. And, of course, the multiplayer modes in various Mario platformers let an advanced player help out less their skilled friends as they chill out in a bubble.

So if Nintendo wants to help out novice players, they can… Let players choose which levels they take on. Change the stage layout to be more forgiving. Introduce other characters who are easier to play as. Help out players who repeatedly die with a guide, a power-up, or a level skip. Or allow players to get a friend to jump in and help out.

Seamlessly shifting

So as we can see, simply getting through a Mario level - or an entire Mario game - is supposed to be of a pretty standard level of difficulty. It might change from title to title - some are slightly easier, others are a little tougher - but on the whole, this should be suitable for an average player.

But as you play, there are all sorts of ways to change that difficulty level. Intimidating trials like enticing extra pick-ups, super hard bonus levels, and tricky optional conditions are there for those who demand a greater level of challenge. Whereas generous assists like invincible player characters, co-op modes, and skippable stages are there to help out players who find the baseline difficulty too hard.

And so, ultimately, Mario games do have difficulty modes - because we can think of these three pipes as easy, normal, and hard.

But they’re very different to a more traditional difficulty setting. There, these pipes are separate and siloed. A player is sorted into one of the three at the very start of the game - and typically stays in it for the duration of the adventure. But in a Mario game, the pipes are all connected, and so the player seamlessly shifts between them as they play. Perhaps accepting help when they become frustrated, but then pushing themselves to take on more challenges as they become more confident.

And so instead of asking the player to predict their level of skill before the game even begins, Mario games let players opt in and out of challenges midway through the game… or even midway through a level. At every step of the journey, players get to ask themselves… “can I do this”?

And Nintendo wants them to say “yes”.

Because even though Nintendo adds in all of these features to help out beginner players, it still understands the value of difficulty.

In an interview about Star Fox Zero, Miyamoto said “part of the fun of taking on a challenge is that the challenge has to be a hurdle that you overcome. Simply lowering the hurdle doesn’t necessarily mean that the challenge will be fun. What’s fun is you mastering the skill and having that sense of accomplishment—of achieving something that’s difficult.”

So part of this three pipe design is making sure that players are always encouraged to move up - to stop using assists and to try taking on harder challenges. And this is done in a number of ways.

For one, assists are usually a one-off, temporary help - a thing that helps you get through that one specific level. But then it goes away and you have to do the next one yourself.

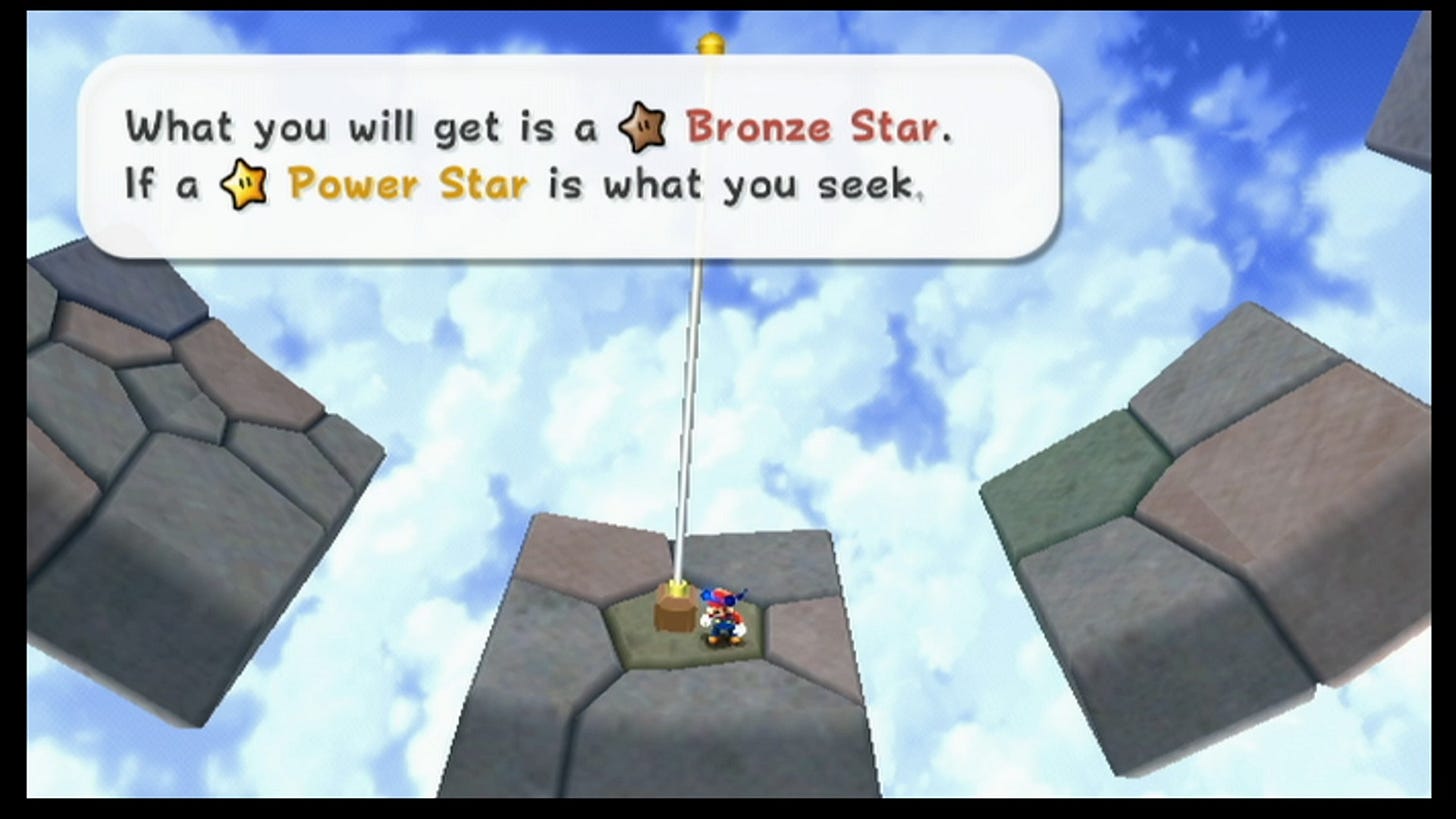

Also, using assists usually means that you don’t get a true reward. In Mario Galaxy 2, using the Cosmic Spirit nets you a bronze star instead of a proper power star. You’ll need to come back to get the real deal. In Super Mario Bros. 2, you won’t unlock World 9 if you got to the ending by using warp zones. And playing on easier mode in Super Mario Run means your purple coins aren’t saved.

Plus - Nintendo often hides the assists altogether until players truly need them. On New Super Mario Bros. Wii, the developers spent a long time deciding on exactly how many times you have to die before the Super Guide shows up.

Late Nintendo president Satoru Iwata says “it's fine if it appears when you're on the verge of tears, but [not] if it pops up when you're still brimming with determination to do it. Getting that timing right is extremely important”.

Nintendo also encourages players to tackle greater challenges by letting them proudly display their achievements. Ever since Super Mario Bros. 2, the games have used shining stars and medals on the file select screen to let players show off that they’ve finished the game’s hardest challenges. Further still, in some games, if you ever use those assists then the stars on the file select screen will no longer shine. It’s a way to stop expert players from giving in to temptation to use an assist tool.

And finally, Nintendo makes sure that being skilful doesn’t inadvertently make the game easier. What I mean by that is… in early Mario games, completing optional challenges would net you useful rewards. In Super Mario World, finding all five dragon coins gives you a 1-UP. And in New Super Mario Bros., the star coins let you unlock toad houses with 1-UPs and power-ups.

This means that showing skill - and proving that you’re an expert player - rewards you with stuff that actually reduces the difficulty level. It’s a nasty negative feedback loop that inadvertently pushes you out of the top pipe.

In more recent games, then, those expert-level challenges are instead used to unlock even more difficult stages. They reward skilled players with even more chances to show their skill.

All of this means that players are put off from using the assists, and encouraged to seek out ever greater challenges. But, then again… players don’t actually need all that much encouragement to make a game harder. Provided it’s fun, of course. Just look at how players create self-imposed challenges like speed running, no coin collection, or the Mario nipple% run. It’s good to track the player’s achievements to provide a sense of progression, but players will often surprise you in how they find ways to wring out more difficulty from a game.

Case Study: Wonder

So let’s finish by looking at how all of this comes together in Mario’s latest game: the wonderful Super Mario Bros. Wonder.

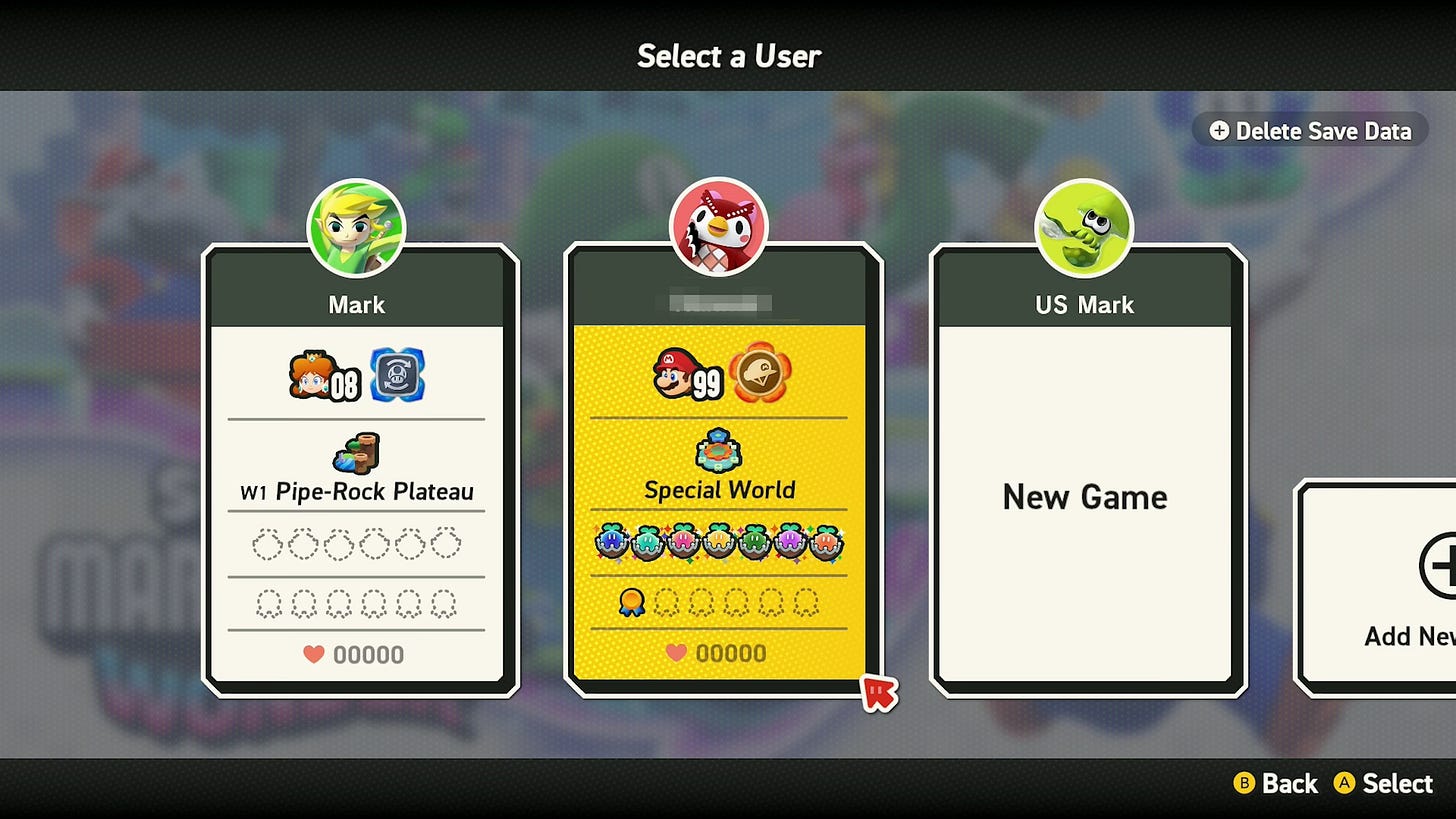

Things start with the character select screen - Mario, Daisy, Toad, and so on all play the same, but Nabbit and Yoshi are cordoned off as easy-mode characters who can’t take damage from enemies. However, you can switch character at any time from the menu - and you may be enticed to do so, when you learn that these easier characters can’t make use of the game’s fun new power-ups. There’s no “Elephant Nabbit” for instance.

You can also change the difficulty by using the game’s new badge system. Some make the game easier - like, one saves you from falling into pits, another gives you a mushroom at the start of every level. But other badges make the game more difficult, letting advanced players take on a self-inflicted challenge like going invisible or forcing Mario to continuously hop.

You can only wear one at a time, and you’re encouraged to change your current badge whenever you die.

The game’s structure is designed to let players pick and choose the levels they want to play. To finish a world you’ll need to own a certain number of wonder seeds - in Pipe-Rock Plateau you’ll need 14 of them to tackle the end boss. But, between the levels, secret exits, and even the shop, there are more than 30 of them in this hub - meaning you can skip some stages entirely if you choose. This also allows Nintendo to drop in a few harder stages that advanced players can enjoy - and beginner players can ignore.

Nintendo game designer Koichi Hayashida says “up until now, 2D Mario games have been in a format where players complete each course in sequence. But in this title, players who want a challenge can start with a difficult course, and beginners can start with an easier one”.

Each hub also hides a secret exit which takes you to a special world, filled with the hardest levels in the game. And, again, they’re entirely optional. There’s even the customary end game level which you can only unlock if you’ve aced every level in the game. That involves getting every wonder seed, picking up all of these 10 flower coins, and getting to the top of every flag pole. This stuff is all represented by medals on the title screen so players can proudly track their progression throughput the game.

Also: the game is multiplayer, so you can get a friend to help out. And the new online standee system lets you place down checkpoints ant any point in a level.

And in each level, there are lots of opportunities to push your luck - including the 10 flower coins, which are this game’s version of the star coin. They don’t confer any advantage on the expert players who get them. In fact, in this game, it’s the less skilled players who are rewarded. If you die you’ll unlock a special bonus “Coins Galore” level which gives you a chance to earn some more 1-UPs and cash to spend in the shops.

So Mario Wonder perfectly shows off this excellent bit of design. The main path through the game is of a reasonable level of challenge - but Nintendo offers plenty of ways to make things easier if the player needs it. And, on the other hand, the game keeps offering ways to make things harder. Enticing little challenges to keep expert players happy. And it’s entirely up to the player which path they’ll take.

But I don’t think this shows that Nintendo has finally solved that decades long problem - and I expect they’ll still be experimenting with ways for players to change Mario’s difficulty. In an interview for Wonder, a Nintendo staffer explained that long time Mario designer Takashi Tezuka wanted a system that could change the difficulty level of the entire course, in real time, at the push of the button.

It proved too complicated for Wonder but, says Tezuka, “you never know, right? Maybe it’ll be in the next game”.