The Secret to Designing Mysterious Games

Enter into the unknown

One of my most memorable gaming experiences of the last few years, happened near the beginning of The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

So I finished all the tutorial stuff on the great plateau, I dropped down into Hyrule, and I started to head out and explore. And not too long after that, I trekked up a hill and noticed a strange shape in the night sky.

What the heck is that?

It looked like a gigantic flaming dragon, weaving through the moonless sky. Is that an enemy? Is that a friend? I have no idea. I started to run towards it - I didn't care if it was dangerous, I just wanted to know what it was.

But as soon as I got close, the blood moon appeared - that's a mechanic that stops you in your tracks and resets all the enemies in the world - and when it finished, the dragon was gone. It had completely disappeared.

This was like a UFO sighting. Was that even real? Did that actually just happen?

This experience, well - it gave the game an incredible sense of mystery. And that is one of my favourite sensations that a game can give: Mystery. The unknown. The unexplored. The unexplained.

And in the last few years there have been some fantastic games that really evoke a sense of mystery. From Tunic to Outer Wilds, and from Animal Well to The Witness, these are games that give players the opportunity to truly uncover the unknown.

So in this video I'm going to look at these games - and plenty of others - to help figure out the mystery of making a good mystery. And so if you'll join me on this trip into the unknown, I'm Mark Brown, and this is Game Maker's Toolkit.

What Makes Something Mysterious?

So: we have to start by asking - what makes something mysterious?

Well, I think it's about something being kept from you. Something being unexplained, unknown, uncharted. LOST creator JJ Abrams calls it the "withholding of information, [and] doing that intentionally".

And when it comes to a video game, well, there are many things we can conceal from the player.

Fig. 1 - The Locked Door

Perhaps the quintessential mystery is the locked door.

Take the game Tunic - an adorable Zelda-like adventure about a tiny fox on a little quest. Throughout this low poly landscape you'll find locked doors, shut gates, and other impassible obstacles - like tombs that are too dark to explore, and enemies that are too tough to fight.

And at the top of the world, at the very peak of this snowy mountain, there's a gigantic stone gateway that towers over your character, and seems to have no keyhole and no door handle...

A locked door is inherently mysterious because the player is left to wonder what's behind it - and to wonder how they'll ever open it.

And we see locked doors throughout mysterious games. The imposing gateway to Sen's Fortress in Dark Souls. The golden statue room in Super Metroid. The black egg in Hollow Knight. And the Moai head in Spelunky's ice caves. Each one becomes lodged in your head as you play - an unresolved question of what's behind the door? And how do I open it?

Tunic designer Andrew Shouldice calls these things 'paths into the darkness', and explains that "I like having lots and lots of paths in my head when I play video games. Lots of loose ends that I'm excited about. And I think the reason is that curiosity and speculation is fun".

But you do have to be mindful of how many locked doors the player is expected to juggle. Because each one adds to the mental load, and having too many mysteries can become overwhelming. Like, in the game Lorelei and the Laser Eyes there are so many things to keep track of - so many locked doors, locked boxes, locked safes, locked clocks - that you can feel utterly swamped by the secrets.

This was a big concern for Billy Basso - the designer of Animal Well, who says "I am conscious of how many things I am dangling in front of the player at any given time. It can be fun to tease a player with a door that is locked from the other side. But it can be overwhelming to walk into a room and see six doors connecting to different areas."

So he intentionally limits how many loose ends you can have in your head - making sure they're dolled out slowly throughout the game and the world map. And he even pulls off some clever tricks - for instance, instead of having a locked door between two rooms, he can have a destructible wall that can only be blown up from the right-hand side.

This way you still get to create a shortcut between two areas - but from the left-hand side, the player has no idea that there's a pathway at all.

Fig. 2 - The Rules

Another thing we can conceal is the rules of the game itself.

Take Rain World. A game about a squishy, slug-like cat just trying to survive in a harsh urban landscape. While the game starts with a few tutorials - teaching you how to get food, fill your belly, and hibernate - the rest is deliberately vague. You're left to wonder about everything else: like, what are these symbols and what do they mean? How do you open those strange gates? And what the hell is that creature before me?

Designer Joar Jakobsson was inspired by his experience of being a foreign exchange student in South Korea - a place where he could barely read the signs or hold a conversation, and so felt like a 'stranger in a strange land'. Rain World beautifully captures that feeling by being intentionally obtuse - and by refusing to explain most of the rules of the game.

So playing Rain World feels like exploring an alien landscape, filled with unknowable creatures. Where other games might explain every mechanic, rule, and system through tutorials and pop-ups, Rain World stays schtum - knowing that a game is more mysterious when the player is kept in the dark.

It's not just Rain World, of course. The Souls games are infamous for their inscrutable gameplay - whether that's cryptic gameplay stats, seemingly pointless items, incomprehensible NPC dialogue, or bizarre overarching systems like world and character tendencies in Demon's Souls.

I still don't really know how those work.

And Starseed Pilgrim is another notable example. This is a game about planting seeds to grow platforms. That much is obvious. But everything else is left unexplained. What do the different seeds do? How do platforms interact? What do hearts do? How do I break out of this loop? And - most importantly - what is my actual goal?

Developer Droqen says "I never added clear instructions because I have no love for those, and I learned that the world became more interesting that way. As it turns out, mystery and wonder are powerful emotions."

But remember - there's a fine line between something being intriguing and something being confusing.

Because if you're not careful, well - consider how Rain World's standoffish refusal to explain some of its most fundamental rules means that a certain number of players are just going to bounce off and give up. They'll either seek out a guide, or stop playing altogether. I mean, I'll readily admit that it took at least two false starts with Rain World before I finally got it.

So it's important to be extremely intentional about which things you choose to leave unsaid. Game designer Rune Johansen says "it’s important to be conscious about which elements of the game should aim for usability and which should aim for ambiguity".

You can start with things that are optional - like how Super Metroid never explicitly teaches you how to wall jump or hop up to high places with bombs - but it also never requires these advanced manoeuvres to complete the game.

Or focus on things that should be inherently unknowable - like, in Rain World, you have to learn about the various predators through careful observations of their movements - but it makes sense that you wouldn't immediately know how an animal thinks. And, in Zelda, it's understandable that you wouldn't know the outcome of mixing up various fantasy ingredients in Link's cook pot - or the nature of a mythical dragon in the night sky.

Fig. 3 - The Landscape

Mystery can also come from the landscape.

Consider Elden Ring - a game about exploring a gigantic fantasy continent. It's a game of a thousand heavy metal album covers - like the barren, rot-scarred swamps of Caelid, the imposing stone walls of Stormveil Castle, and the underground throne of a dead giant.

Critically, the game tells you almost nothing about what's over the horizon - or even what's around the next corner, or what's inside that cave. Where other games might give you a detailed map, or use a compass to point towards your destination, or constrain your travels within walls and barriers, Elden Ring simply lets you explore.

The game's director, Hidetaka Miyazaki, says "in order to have adventure, in order to have discoveries, you need to have some unknowns."

It's not just Elden Ring - mind you. This is baked into the DNA of the Zelda franchise, which started out as a way for creator Shigeru Miyamoto to capture his childhood memories of exploring the Japanese countryside. And Riven is all about exploring a strange world - even down to text and dialogue being presented in a made-up fantasy language.

But, again - there's a delicate balance between giving a player an interesting landscape to explore, and letting the player become completely lost and confused. But instead of spelling things out with detailed maps - consider letting the player be the one to chart their adventure. Let them place down pins, stamps, screenshots, and notes, just like you would if you were really exploring a strange new world.

Also - be careful not to undercut the player's sense of wonder and curiosity, with a chatty companion character who over-explains everything you see. Compare the eerie silence of The Talos Principle, with the yapping band of explorers in its sequel.

Fig. 4 - The Enigma

Finally, we can conceal information about the game's narrative.

Take Outer Wilds. This is a game about exploring a simulated solar system while being trapped in a 20 minute time loop that happens to reset just as the sun explodes. And from the very moment the game begins, the game sets up a number of tantalising questions. Like why are we in a time loop? What happened to the previous civilisation? And what is the eye of the universe?

And then as you explore the galaxy, jumping from planet to planet, more mysteries are revealed - from massive celestial secrets like a teleporting quantum moon; to smaller, more mundane mysteries like a missing explorer. Narrative designer Kelsey Beachum says "at its simplest, Outer Wilds is a game about finding answers to questions about the world around you."

Other games built around a mystery include The Forgotten City - another looping adventure, this time about time-travelling to a secret city underneath ancient Rome. And Her Story - a whodunit detective game about trawling through a database of police interview clips.

These games have a tantalising question at the heart of their narrative - and promise to answer it by the end of the game. This turns the entire game into one long mystery - and everything you do serves to slowly unravel that enigma.

But designers must ensure that players, well, even care about unravelling the game's secrets.

Because, well in its final form, I think Outer Wilds makes players incredibly motivated to go out and explore - but designer Alex Beachum admits that it wasn't always this way, saying "the really hard part was figuring out how to actually get players to ask these questions and how to make them curious - without us just like beating them on the head and telling them what to do."

And so he had to employ all sorts of tricks to spark curiosity in players. For instance: he found that he couldn't be too subtle, as players would only be drawn to things that were particularly weird - like the quantum moon - or particularly eye-catching - like the exploding space station.

And he discovered that players would be most motivated when the narrative felt personal and directed at them. So that's why the Nomai statue turns to look at you in the museum. And why the museum's curator, Hornfell, makes a point of asking you what you want to do when you get into space - instead of just telling you what's out there.

Alex has a talk at the Full Indie Summit where he explains all the tricks he used to make players curious - find a link to this, and all of the other sources - in this video's description.

Questions and Answers

So: we can make a game mysterious by withholding information from the player. Perhaps the contents of a locked door. The rules of the game. The landscape of a fantasy world. Or unknown information at the heart of the game's narrative.

All of these approaches are quite different - but I think they all serve the same purpose: by concealing information from the player they create questions in the player's mind. What's behind that door? What is that creature? What's that in the distance? What happened to the Nomai?

And each question creates a curiosity gap - that's the space between the information we're given, and the information that's being withheld. Which is a powerful force that can motivate a player to keep going until the question is answered.

But how does the player actually answer the question?

Because in almost any other medium, the answer to a mystery simply comes from continuing to read or to watch until the secret is revealed. What is the smoke monster? Well, you'll find out in season five. Maybe…

But what makes video games great is that the player can be an active participant in answering the question. So in a game with locked doors, we can ask the player to literally venture out and find the necessary key. In a game about a mysterious landscape, the player closes the curiosity gap by going out and exploring.

And in a game with obtuse rules, the player can make sense of it through careful observation, scientific experimentation, and - often - a little trial and error. Spelunky designer Derek Yu says "that is the fun part about games - discovering things on my own, making my own mistakes".

But, you know what? If we truly want the player to feel like they're uncovering some great mystery - I think we need to go a little further than that.

Knowledge

So let's go back to Tunic, and that gigantic door at the top of the mountain.

Because while you absolutely need to find a shiny golden key in order to open a normal door, the mountain door actually doesn't have a corresponding key. In fact, you won't find any item, ability, power-up, or upgrade that will let you open this gate.

Instead, what you need is knowledge.

Now I don't want to completely spoil the game, so let's just say... eventually you'll learn about some special way of interacting with the game that will make stone doors swing open. Same goes for using big yellow pads, or interacting with mechanical totem poles, or even upgrading your stats.

All of these things are locked not behind keys or abilities, but behind knowledge. Knowledge that you will learn by finding scraps of the game's super nifty retro-style instruction manual.

In fact - this game made me so nostalgic for old manuals that I've made a bonus companion video for all GMTK Patrons, where I look through some of my favourite instruction booklets from my collection. Click here if you’d like to watch that.

Anyway - Tunic's not the only game that does this. Outer Wilds is all about gaining knowledge: on each planet you'll find hints and clues for how to make progress on another celestial body - perhaps telling you how to dive into the depths of Giant's Deep, or how to make your way through Dark Bramble.

Riven has you paying close attention to animal noises and a cryptic numbering system so that you can open special locks. And the game Chants of Senaar is all about untangling a number of foreign languages so you have the words to figure out riddles.

Metroidbranias

Some people have taken to calling this group of games Metroidbrainias - because they are like Metroidvanias, only the keys are stored in your noggin, rather than in Samus's armour or in Alucard's inventory.

And if you ask me, discovering these - well, "knowledge-based keys" is one of the most satisfying ways to solve a mystery.

Why? Well, for one - they force the player to pay close attention. You can't just stumble upon a key and then bumble into the lock and make progress. You need to truly understand the clues you're given, and apply that knowledge with purpose and intention. You have to remember things, or even take notes.

Secondly - when something is locked behind knowledge, rather than a specific item or ability, the player can technically answer that question at any point in time.

For instance - the game Fez has a made-up language. And at a later point in the game, the designer gives you a Rosetta stone, of sorts, that lets you translate all of the text into English. However, some players were able to use pattern analysis and other clever tricks to figure out the language... even without this hint. And so they were able to unravel Fez's secrets earlier than most players.

That's a pretty amazing feeling that leads to more personal stories. And it allows for replayability and interesting, sequence-breaking exploits.

And finally - while it can be as simple as, say, finding a number in one location and then inputting it into a keypad in another, these knowledge-based keys can be so much more involved than that. Perhaps requiring you to carefully parse the information, or combine different bits of knowledge, or solve some kind of riddle or conundrum.

For instance, in La-Mulana you need to read different inscriptions to figure out the relationship between a celestial calendar and some massive stone statues. And in Spelunky, you need to puzzle out how to use the life-saving ankh if you want to make it to a special exit.

This adds an extra layer of satisfaction to proceedings - it's not just "oh, I found a key", it's "aha, I figured it out!" You truly feel like you've uncovered a secret, or solved a mystery.

Super Secret Secrets

And ultimately, there's no limit to how cryptic or obtuse these puzzles can be - perhaps even spilling out of the very confines of the game. Or maybe there are secrets that can only be solved by working with other people.

Like, there's a room in Animal Well that contains a strange mural that you can draw on. And in a secret room beneath the ground, you'll find a hint for how to draw the correct image. But, as it turns out, your hint is not enough.

That's because each player is given just one chunk of the mosaic, and it's randomly assigned out of a total 50 possible pieces. And so to solve this puzzle you'll need to collaborate with other players - all pooling individual bits of information and putting them together to get the real clue.

However - it's important to consider just how many players will actually be invested enough to uncover a game's most tricky conundrums. So that's why most designers in this genre have to decide which mysteries are mandatory to finish the game - and which are left optional.

For instance - in Fez, you only need to find 32 cubes to open the final door and reach the credits - but there are dozens more anti-cubes, artefacts, and other secrets to find after that. And Tunic has multiple endings - one if you ignore all the puzzle stuff and just beat the final boss. And another if you dive into the game's most cryptic clues, and discover another path.

Animal Well designer Billy Basso describes his game as having a series of layers - with layer one being a relatively straightforward game for everyone to enjoy. Layer two having more challenging puzzles for secret enthusiasts to hunt down. And layer three containing all the most maddening nonsense that you'll probably need some help with.

Basso says "I think when a game is hard, it's actually an opportunity for [players] to bond with each other and have this shared experience."

The Answer

And so after all that - we finally get the actual answer. Perhaps it's a handy upgrade, or some bonus content, maybe an alternative ending, or a satisfying revelation.

But to be honest: if the act of solving the mystery is really fun, then the answer doesn't particularly matter. I absolutely loved figuring out the cryptic game-wide scavenger hunt to open Tunic's mysterious mountain door. But I literally can't remember what was behind it.

So the answer doesn't matter too much - unless it gives away the answer to the game's other questions.

Here's what I mean by that.

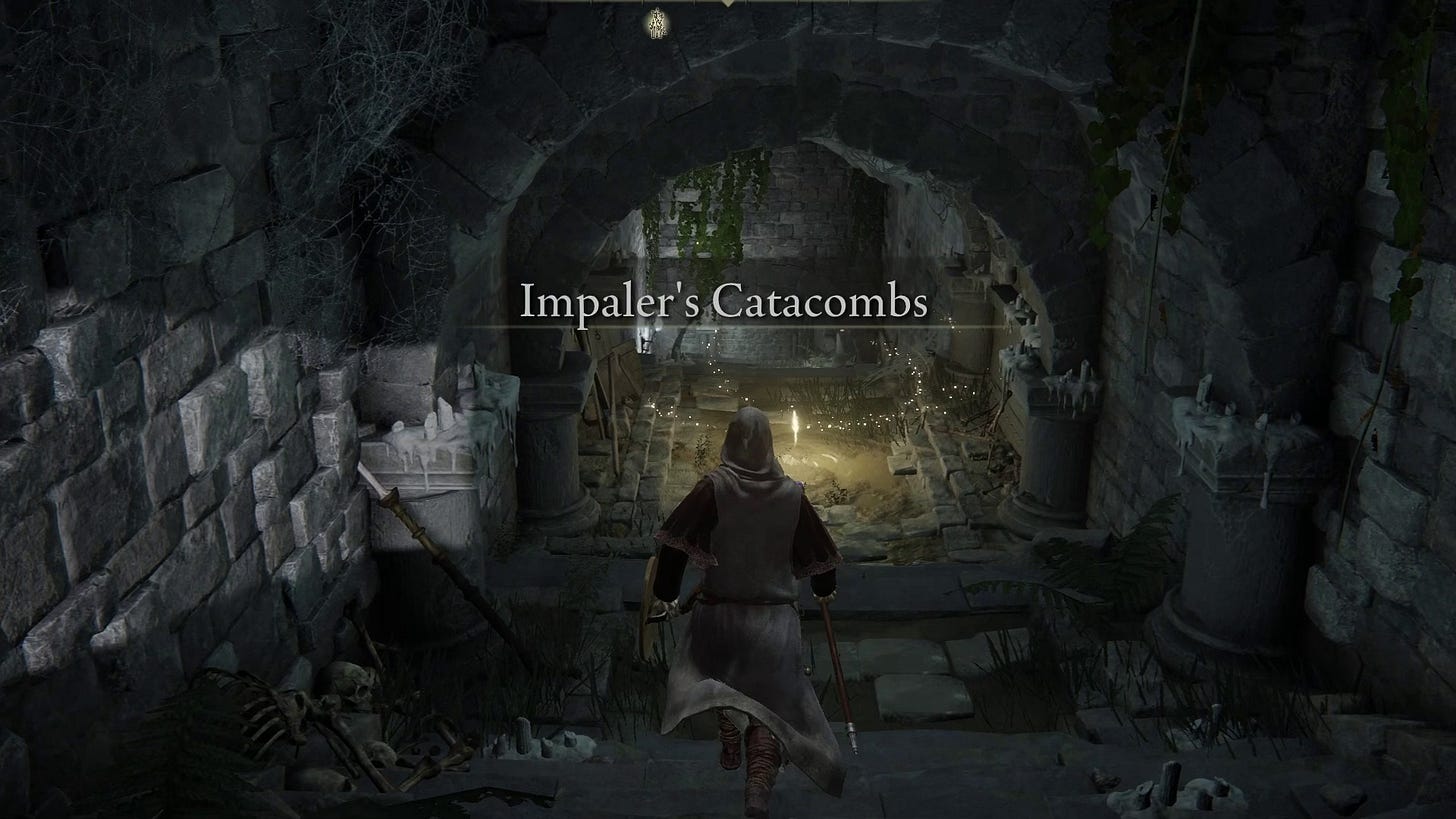

Going back to Elden Ring - the first time you come across, say, a catacomb, it's a potent source of mystery. What is this place? What will I find inside? Well, the only way to know is to ready your sword and shield and dive on in.

But then later, you find another catacomb. And then another. And another still. And each one seems to cohere to a strict template: there are white flowers, there's a boss, and your reward for beating the dungeon is almost always a new spirit ash.

Soon enough, the player will start to notice the pattern, and can now predict the answer to a question before they've even had a chance to answer it. Which essentially robs the question of its mystery.

So while it's tempting to use a repeating template to design content - especially if you're making a massive game that requires huge amounts of stuff for players to discover - it's important to make sure players can't predict the answers to everything.

So this can be achieved by making sure you also litter in a few completely unique areas that don't follow any kind of pattern. Or by establishing a pattern... and then intentionally breaking it. Like how in Super Metroid, the game establishes that item rooms are safe places to get a new ability or upgrade - but then you get the bomb from a certain room, and...

Oh! I wasn't expecting that! Now you'll know not to take things for granted.

Invisible Questions

So - that's it, right? A game can pose questions - and the player can discover answers.

Well - this neat and tidy categorisation does miss one thing. Because for the player to ask a question, they need to know that something is being concealed in the first place. You can only wonder what's behind a door... if you know that the door exists.

But what if you never actually show the door to the player?

Well, let's talk about The Witness.

So this is a game about solving back-of-a-cereal-box grid puzzles on a beautiful Myst-like island. And those puzzles are pretty neat. Each batch of head-scratchers is based on some special rule - perhaps shadows or symmetry or sound or separation - and you'll need to figure out the underlying language of the puzzle design in order to solve all of the grids.

But - there's more to The Witness than meets the eye. Because after hours and hours of staring at grids and lines, you'll perhaps start to notice something. Like, maybe you've climbed all the way to the top of this mountain, you look down at the river below and you think... wait, doesn't that look like one of the lines I've been drawing on these grids?

And so you press the button - the one that, so far, you've only ever used to draw on a grid panel. Only this time, you're drawing on the world itself. And - holy crap! There are puzzles in the environment! Forget those poxy grid panels - every path, every flower, every cloud could now be a puzzle.

This mind-blowing moment of revelation changes everything. It turns out that there are questions that we didn't even know we could answer. Invisible questions. Ones that make you ask "what else is the game hiding?"

Tunic developer Andrew Shouldice says "my very favourite sort of game is one where as you play, you don't just find new things in your path, but suddenly the entire path that you've traveled becomes littered with question marks."

And it's not just The Witness. The first time you hit a wall in Dark Souls and it disappears in a puff of smoke - well, your entire understanding of the world just changed. What else could be hidden behind one of these illusory walls? Chests? Goodies? Surely not an entire extra area...

Same goes for realising that you can input codes into Fez by jamming on the shoulder buttons. Or that you can escape into the user interface in Super Mario Bros., and run straight past the level goal.

Uncovering one of these mysteries feels like discovering a true secret about the world around you. And for that to be the case, these invisible questions pretty much have to be entirely optional. Something that only certain players will stumble upon.

The Witness designer Jonathan Blow says "it had to be legitimately likely that you could finish the game and never see that stuff. Like you had to take an extra step of noticing something on your own to find that."

/Conclusion

So: we can make a game mysterious by concealing something from the player.

It could be a gigantic locked door. It could be the rules and mechanics of the game itself. It could be the landmarks and layout of a fantasy world. Or it could be an enigma at the heart of the game's narrative.

Each one of these things creates a question in the players mind.

And then by letting the player be the one to actually answer this question - through discovery, exploration, observation, puzzle-solving, or even working with others, the player gets the incredible satisfaction of being the one to crack the code, and reveal the secret.

But if we don't even let on that there's a puzzle to solve - if we just let it sit there, in the player's view, subtly hinting that there's more than meets the eye - we can give the player a true moment of mystery, as they realise that there's more to this game than they ever thought possible.

Hey! One more story. Lemme tell you about the black monolith in Fez.

So this is a giant, imposing stone totem that can only be cracked open with a very specific set of controller inputs. And to this day... players have never figured out how to open it.

Well. Okay. They actually did. Players got together and literally brute forced the thing - trying of thousands of possible combinations in a mad, and rather inspiring, community project - before finally stumbling upon the right combination. That's, uh, Down, Down, Left Trigger, Right Trigger, Right Trigger, A, and Up, if you were curious.

But the actual intended solution? Like, how were you even supposed to figure out that sequence of buttons without brute forcing it? Well that still isn't known. And players are still debating it, 12 years after the game's release date.

It's either hidden incredibly well, or perhaps designer Phil Fish never even intended to give players a way to figure it out so the game would always have one mystery that would never be solved. The game would always be just a little bit unknowable.