Every year, I use my last video / post on GMTK to celebrate a game that did something different. A game that was innovative, inventive, or just plain smart.

In previous instalments I’ve looked at masterful murder mysteries, micro RPGs, and slithering snake-based adventures. But this year, for 2023, I… need to wind the clock back a bit.

So, back in 2015 I made a video about the new Tomb Raider games. Well, they’re not new now - but they were new then. Anyway - the video was all about how dull the climbing is in those games. Lara Croft’s heroic scramble up a cliff face is represented by… pretty much just holding up on the analogue stick for 5 minutes.

And since that video’s release… well, things haven’t changed much. Alloy hikes up the mountains of Horizon with little need for the player to get involved. And Atreus’s epic climb up the wall of Asgard might have been terrifying for him - but it was no problem for me.

However, in 2023 we finally got a game that dared to do things differently. A game that makes climbing… interesting and engrossing. And so, without further ado, I want to tell you that this year’s most innovative game is… Jusant.

Jusant, from developer DON’T NOD, is a wistful, zen-like odyssey up a massive mountain - and the only way to get to the top is to start climbing.

This post does not contain any spoilers for Jusant, so feel free to watch it before you go play the game.

Character / Controller Connection

Okay, so like I said in the intro, one of my biggest bugbears with Lara’s climbing is that the action on screen feels completely disconnected to the stuff you’re doing on the controller. But Jusant tries something different.

Lemme break down how climbing works.

When we’re on a wall, we can use the left analogue stick to hunt for nearby handholds.

Moving the stick essentially shifts a cursor around in two dimensions - and if that cursor overlaps with a valid handhold, the character will reach out. This system allows us to freely pick whichever handhold we want - even picking between one that is close and one that is far away, simply by moving the stick further away from the centre.

If the character is reaching towards a handhold, we can grab it by using the corresponding trigger - left trigger for the left hand, right trigger for the right hand. That trigger must now remain held down, while we hunt for the next handhold.

So - this system ends up creating a deep connection between what you’re doing on the controller - and what the protagonist is doing on screen.

You push the analogue stick out to hunt for handholds, just like how the character reaches out their arm. The rhythmic switching from the left to right triggers mimics the hand-over-hand movement of real-life rock climbing. And having to hold down a trigger at all times means you’re gripping the controller… in the same way the character is gripping the wall. You let go, they let go.

And DON’T NOD did want to go even further - an early prototype had you controlling both the arms and the legs, using all four buttons on the top of the pad for hands and feet. But that proved overly complicated.

The developer also wanted to involve the controller when jumping to far-off handholds: the idea was that you had to tilt the stick opposite from the jump to coil up and build momentum before releasing the stick to spring up. But this proved difficult to teach and execute. So in the end, the devs settled on holding the jump button to, essentially, charge up the jump.

Now, look, it’s obviously not essential for a game to have you mimic the character’s actions on the controller. But this sort of kinesthetic design, as it’s called, has proven to be a wildly successful trick for making game mechanics more immersive and engaging.

Whether that’s holding the button down for longer to make Mario jump higher. Or pulling back on the analogue stick to reel in a ghost in Luigi’s Mansion. That little up-down flick of the stick to do a manual in Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater. Or the infamous arcade stick inputs needed to pull off a fireball or an uppercut in Street Fighter.

And of course, we have seen this applied to climbing before. The developers at DON’T NOD were notably inspired by the way you clench the controller in Shadow of the Colossus, in order to stay hanging on to each massive monster. And Ubisoft’s Grow Home inspired the use of left and right triggers for the left and right hands. What makes Jusant special, then, is doing all of this stuff simultaneously - and doing it with a human character, rather than a goofy red robot that can bend in unrealistic ways.

Sidenote: It’s very much worth noting that complex wrangling of the controller can prove problematic for players with certain types of motor impairments. I mean, heck, I had to play Jusant in like 20 minute sessions because holding the triggers down for so long played havoc with my repetitive strain injury. So - hats off to DON’T NOD for also offering a number of accessibility settings that can provide easier input.

Rock-climbing Problems

Now - the simple control scheme is not my only problem with the Uncharted-era of climbing systems. You can’t make a game better just by adding in more buttons - or else every game would have you walk around like you’re playing QWOP.

No - the real problem is that climbing requires no thought, no problem solving, no decision making - none of the stuff that makes games great.

And that’s completely at odds with real climbing! Like, did you know that in rock climbing, a route up a wall is actually called a “problem”. And that’s because climbing isn’t just about strength and stamina - but it’s about planning how you’ll move from handhold to handhold. How you’ll shift your body, and how you’ll use different holds, positions, and grips to get to the top.

That’s pretty tough to capture in a video game - but Jusant gets close, with the use of two tools: the rope, and the piton.

So whenever you start a climb, the character will automatically attach their rope to a carabiner that’s embedded in the wall. This means that if you fall, you’ll get snagged by the rope and can climb back up.

But then you’ve got the pitons.

These can be wedged into the wall to create, essentially, checkpoints. Now when you fall, you’ll be caught by your most recent piton. You only have three to spare, though, so you’ll need to use them judiciously. This puts you in charge of when and where to save - giving you more decisions to make as you climb.

However: the rope is not just a clever twist on the save system.

You see, the rope is not infinitely long - it is, in fact, exactly 40 metres in length, and so you’ll need to ensure that you have enough slack to make it to the top of the current climb. That might mean you have to take a shorter route - or work back on yourself to pull out a nuisance piton that’s pulling the rope in the wrong direction.

And the rope is also a proper physics object that can get caught and tangled on different objects.

So at times, the rope is your saviour, but at other times it’s your biggest obstacle.

Though - DON’T NOD does make a couple concessions. For one, there’s a little cheat in the player’s favour: when you are close to a ledge, the rope will magically grow an extra five metres, to avoid those annoying moments where the rope is just a little bit too short to make it.

And also there are relay points which allow you to reset your entire rope to that point.

These are a nifty addition - relays give you a specific point to aim for, so you’re not always simply going up. And without the relay, there would be a strict upper limit on how long a climb could be without giving the player some flat ground to reset their rope. With the relay, though, DON’T NOD could add a few epic climbs where you’re on the wall for significantly longer. It’s such a relief to get to the top and finally let go of those triggers. Phew.

But there’s even more to the rope - because there’s also the way that it greatly expands the available play space.

With climbing and jumping alone, you can only really explore the area that’s immediately around you - there always has to be a viable handhold within jumping distance. But the rope lets you go much, much further.

You can place a piton in the wall, abseil down, and then swing along the wall - this gives you a massive arc to explore, letting you grab onto ledges far away from any handhold. And later, the game takes this into the third dimension. You might have to climb a wall, then dangle down beneath it, and swing beyond the wall to another climbing surface further back.

And elsewhere in the game, DON’T NOD adds in additional challenges - through changes in the environment. Like - you can hit a button to make plants sprout buds that you can use as handholds. Useful. But if they’re in direct sunlight, then the buds will slowly wilt and then die. This forces you to move fast, and use your pitons for safety.

At times, Jusant reminds me of the classic Tomb Raider games, where you have to size up the space and decide how you’re going to use your different jumps to get from A to B. A proper three dimensional puzzle game.

Though… I don’t want to oversell it.

Because, okay… I’ll come back to that thought in a minute.

Stamina mis-management

The final thing that makes those old climbing systems boring is that there’s absolutely no danger. No stakes. No peril. In this scene, where Lara Croft is clambering up a wobbling radio tower, she’s absolutely terrified.

But I’m just… not.

Changing the controls to be more engrossing might help me connect more with the character. But I think it has to go further than that.

Earlier this year we looked at the mechanics, dynamics, aesthetics framework, which shows how the game’s mechanics can impact the player’s behaviour, which can, in turn, impact the player’s emotional state. And so game designers can pick game mechanics that will put players in the right frame of mind. Whether that’s making the player feel like a badass, or feel absolutely terrified.

And if you want players to feel scared, then you probably need some sort of consequence for failure. And in these sections, Tomb Raider just… doesn’t.

But, well, neither does Jusant, really.

For one, you simply cannot die in Jusant. There are invisible walls to stop you from walking off a cliff. And because you’re automatically attached to the rope at the start of every climb, then letting go of the handholds will just send you back down - or back to the last piton you placed.

And even then… it’s extremely rare to ever fall off in Jusant. The most likely reason would be to run out of stamina.

You see, completing a valid action will deplete some stamina - a tiny amount when grabbing a handhold, or a lot when jumping.

Now DON’T NOD went through many iterations of this system, including having independent stamina gauges for each arm. A chunk system where if you deplete an entire chunk, it wouldn’t regenerate until you touch the ground. A system where you could only regenerate stamina while hanging from the rope. And a system where if you run out of stamina, you’d have to manually descend all the way back to the ground and start again.

Ultimately, playtesting showed that none of these were a good fit. Some felt overly punitive, others disrupted the climbing flow, and others were difficult to communicate to the player.

In the end, DON’T NOD went with something far more simple: your stamina drops, but it can be replenished, at any time, by clicking in the left stick. However, big actions like jumps will permanently reduce the size of the stamina bar until you’re on flat ground. So the more you jump, the more often you’ll need to rest.

This means that the only way you can ever really run out of stamina is to completely ignore these obvious prompts to stop and rest for a second. And so stamina management just ends up being… like, a little nuisance thing to nurse. Never something you’re really worrying about - like you might in, say, Shadow of the Colossus.

And this means Jusant almost never makes you feel like you’re in any real danger.

Developer Intentions

But here’s the thing… that’s not what DON’T NOD was going for.

The developer tells me that the intention for this game was to make a peaceful experience without pressure. A chill, atmospheric adventure - inspired, primarily, by Journey. And so the developers deliberately removed aspects that would cause friction and frustration.

That’s why I don’t want to oversell the game’s problem-solving gameplay: there’s some smart ideas in here, but nothing that’s going to cause you significant trouble. And that’s because it would disrupt DON’T NOD’s intended flow.

And developer intention… is something I’ve perhaps struggled to consider in my previous videos.

Like, let’s go back to the climbing in Tomb Raider and Uncharted. Were the developers ever actually intending this stuff to mimic real-life rock climbing? Probably not. As I explored in this video on mixing genres, the climbing sections are just supposed to be something simple to do as a bit of downtime between the more involving combat sections.

And so, at times, I have criticised games because they haven’t incorporated some mechanic, system, or idea… even though the games were never trying to do that in the first place. I wanted Spider-Man to have a complex web-swinging system that took skill and effort to master. But Insomniac just wanted every player to feel like Spidey from the moment they picked up the controller.

And maybe this is me getting older and wiser and realising that, hey, not everything is supposed to revolve around me. I am not the protagonist of reality. Maybe this is from talking to more developers about how games get made. Maybe this is from becoming a game developer myself - and having my own intentions! Whatever the case, if there’s one regret I have about past episodes of GMTK, it’s this.

So instead of saying - hey, I wish Jusant was more challenging and more punitive - I’ll instead take the game on its own merits.

Then I can look at the stuff I like about the game - the immersive control scheme, the clever rope physics, the thoughtful checkpoint system - and stash that in the ol’ toolkit as a good example to point to. And for the rest - well, instead of seeing it as something for Jusant to fix, I can see it as an opportunity, for another developer, with different intentions, to tackle in the future.

What I’m saying is - hey, Square Enix, if you want to give the next Tomb Raider game a new identity… play Jusant. It’s on Game Pass! It’s great!

Honourable Mentions

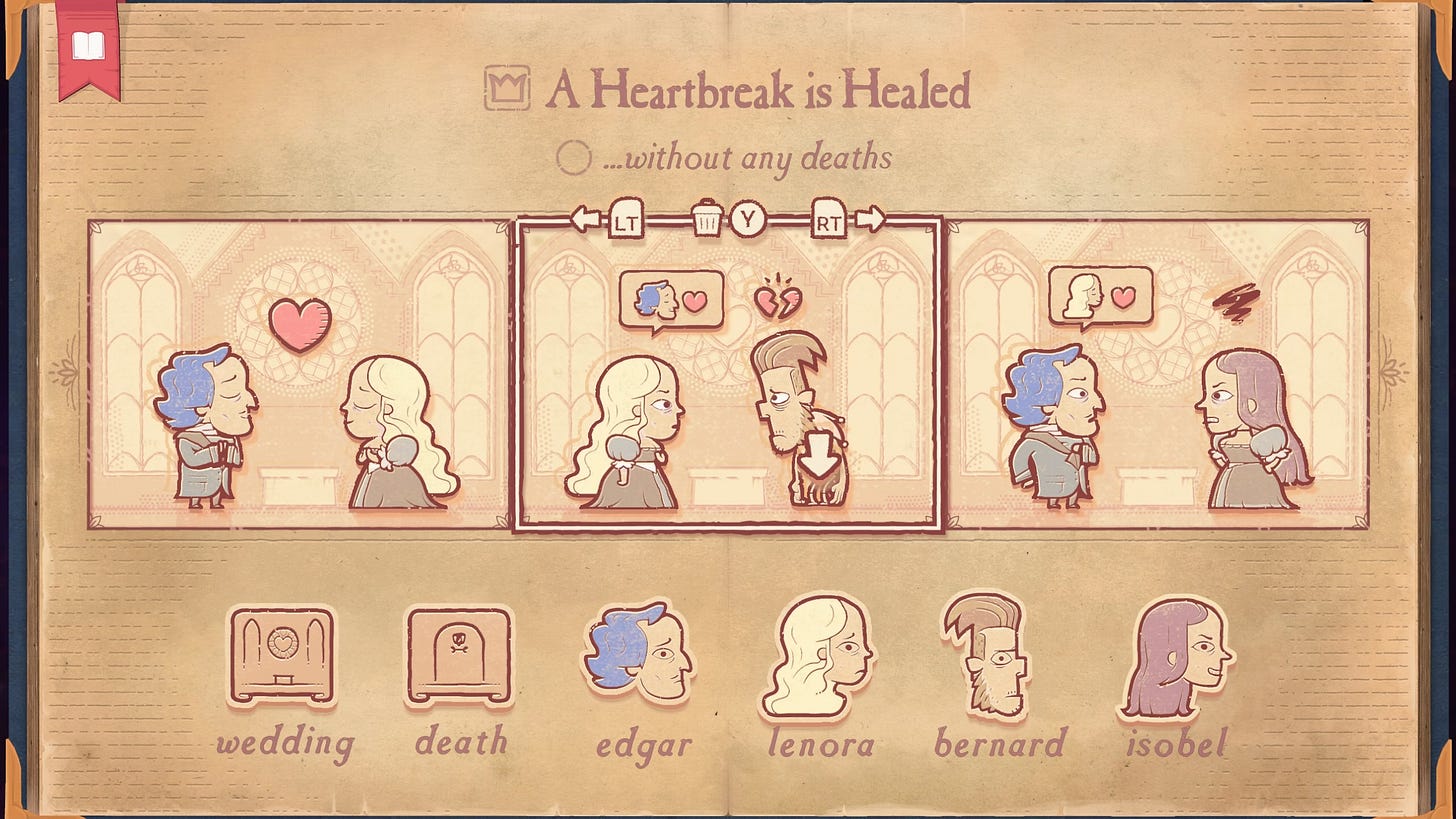

Storyteller is a wildly ambitious puzzle game, where you are given an empty comic book and a title. Now you have to fill in the spaces with characters, objects, and themes, to make a narrative that fits the prompt. It plays on visual language and, well, story telling to make a completely new type of puzzle.

Terra Nil is a city-builder with a stark ecological message. Instead of stripping a planet for resources, the game is actually about undoing the greedy grubbing of a previous generation. So you have to carefully plop down buildings that will replenish and revitalise the land - and then pack everything up and bugger off back into space.

Shadows of Doubt is an epic detective simulator. The game generates a city block, filled with hundreds of people who have lives, jobs, relationships, and daily routines. When one of those citizens is murdered, you’ll have to work the case in order to find the killer - using stuff like fingerprints, CCTV recordings, and employee databases. All neatly organised on a caseboard, complete with pins and red string.

Pseudoregalia is a Metroidvania that looks like a lost N64 game, and has some of the best 3D platforming in years. You can mix and match various moves - like a long jump, a ground pound, and a wall kick, to navigate blocky obstacle courses. And, if you’re good enough, break the game’s sequence entirely. Expect to see this one at speedrunning events.

Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom deserves a nod for its brilliant Ultrahand system. This thing lets Link fuse things together in order to make vehicles, weapons, and problem-solving tools. It’s elegantly designed, to make it easy to build whatever you want. And it means you can play the game in pretty much any way you desire. There’s a full video on the channel about how Nintendo made it.

Viewfinder is a mind-blowing technical masterpiece. You can take a photo, and then place down the Polaroid to summon the photo’s contents into the world. It never stops being impressive. And it’s also just a very good puzzle game with lots of clever twists on this central mechanic.

And Chants of Sennaar is a game about language. You must decipher an unknown alphabet in order to make your way up a massive tower. You’ll have to use contextual clues and leaps of logic in order to guess what each letter symbolises. And then do it all again, with a fresh set of glyphs, on the next floor.

Wow - turns out there were loads of incredibly innovative games this year!

Thanks so much for watching or reading Game Maker’s Toolkit this year. In the last twelve months I’ve made videos / posts on The Sims, Zelda, Banjo Kazooie, Resident Evil 4, detective games, the MDA framework, 2D cameras, and Valve’s playtesting approach. There was another record-breaking game jam, a new series about short indie games, and four devlogs for Mind Over Magnet - which you can now wishlist over on Steam.

I’ll see you in January, for the - can you believe it - tenth year of doing Game Maker’s Toolkit. Time flies when you’re having fun.