What Makes a Great Detective Game?

How Obra Dinn, Paradise Killer, Shadows of Doubt and more make crime-solving fun

Way way back in 2017, I made a video that essentially asked... where are all the good detective games?

I mean - sure, there are plenty of fun games where you play as a detective. Like The Wolf Among Us and Sherlock Holmes. But - in terms of the game mechanics - they never actually made me feel like I was doing any real detective work.

For that, I had to dig much deeper. I'm talking about ancient PC artefacts, and obscure indie titles, and unfinished Itch.io demos, and bizarre FMV games.

But! A lot can change in five years.

Because since that video came out, we've seen an explosion of new detective games. At least one of them made in direct response to that original video!

These new games have given me a whole new perspective on this design challenge - and they've made that old video... pretty much completely outdated.

So it's time to exhume the body, re-open the case, and ask - again - what makes a good detective game?

So - I played a bunch of detective games for this post. Everything from Disco Elysium to Judgment, and from Frog Detective to The Murder of Sonic The Hedgehog. All wonderful games, to be sure. But I was hunting for games that truly made me feel like a detective. And in my search, I realised that those titles fit into three different categories.

I'm going to call them deduction-style games, contradiction-style games, and investigation-style games.

Deduction Style Games

Let's start with deduction-style games. And the ultimate example for this type of game is Return of the Obra Dinn - Lucas Pope's 1-bit murder mystery masterpiece.

Okay, so in this game we're on board a 19th century merchant vessel where all 60 passengers are dead or otherwise missing.

As an insurance inspector, our job is to fill out a log book by jotting down everyone's final fate. And to help with this, we can use a magic timepiece to transport ourselves to a freeze-frame vignette, showing the exact moment of each person's death.

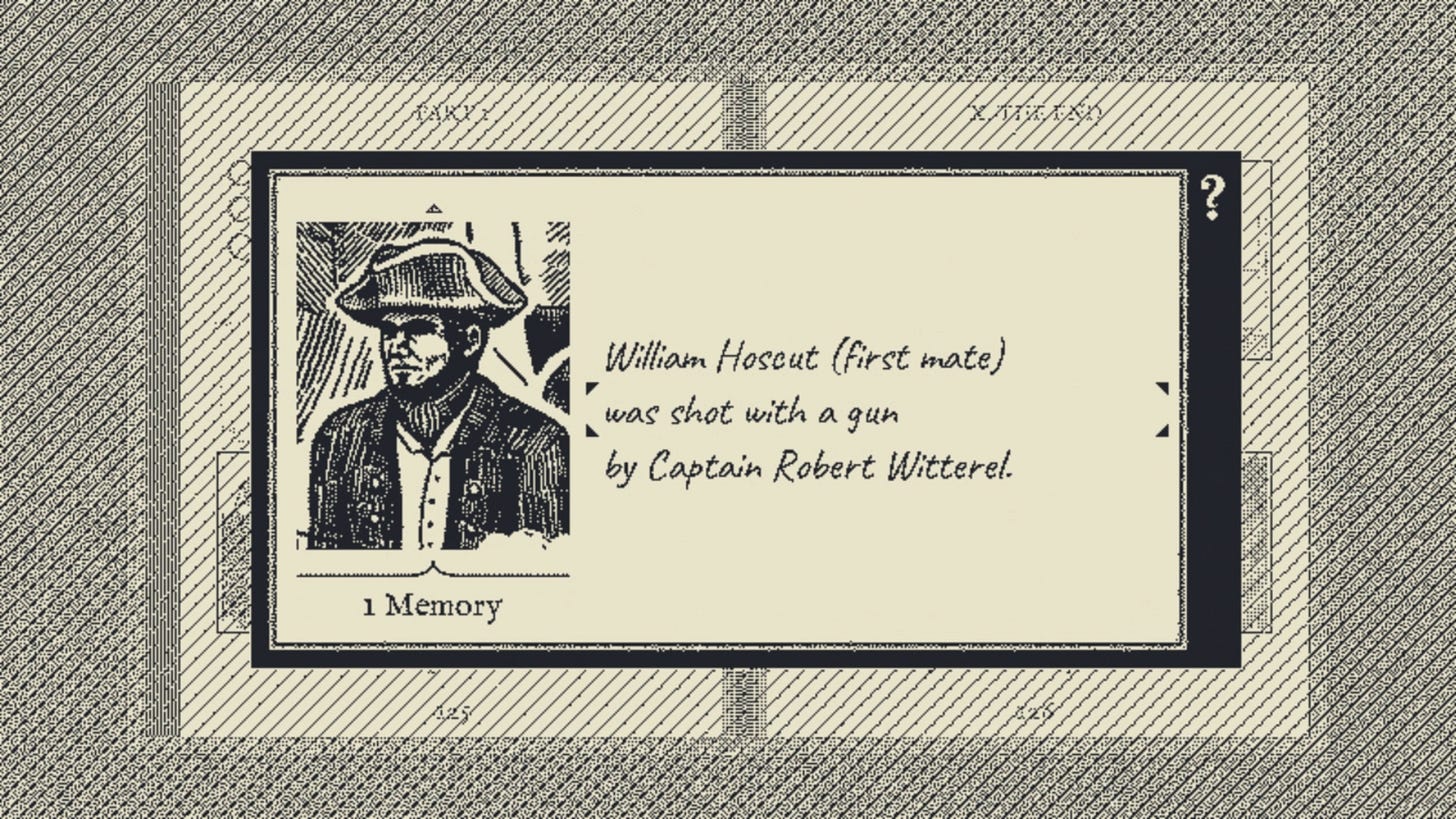

In one vignette we hear the words “Captain, open the door!”. Then a gunshot. And then see a man being shot in the chest.

From here, we can gather clues and information - including those final words of dialogue, and the accent they're spoken in. The location of each character, the outfits they're wearing, the objects they're holding, and so on.

And we can then use these clues to answer the questions in the log book. So now we know that the man was shot by the captain.

But... who is he?

Ah, well. You see, the clues alone won't always provide the answers we need. In fact, no where on this ship will we be directly told this person's name. So, instead, we'll have to deduce his identity by cleverly interpreting the other facts and clues.

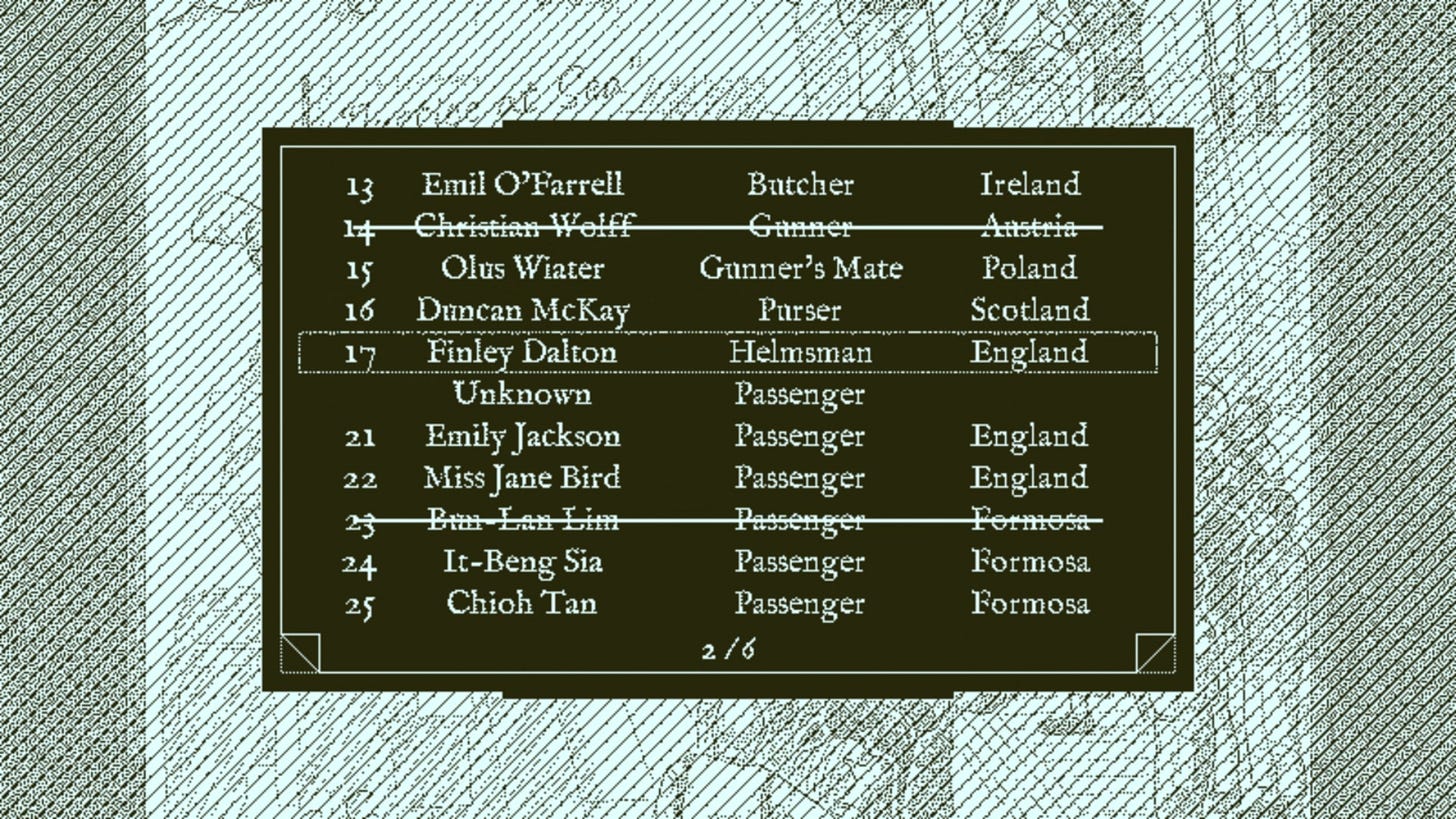

For this one, we will later hear the captain's last words - admitting that he shot Abigail's brother. From the crew roll, we know that Abigail's maiden name is Hoscut. And that there's a man on board with the surname Hoscut. Which means William Hoscut is almost certainly Abigail's brother - and our mystery man getting a face-full of buckshot. Bingo.

Obra Dinn is not the only game that fits into this style, of course.

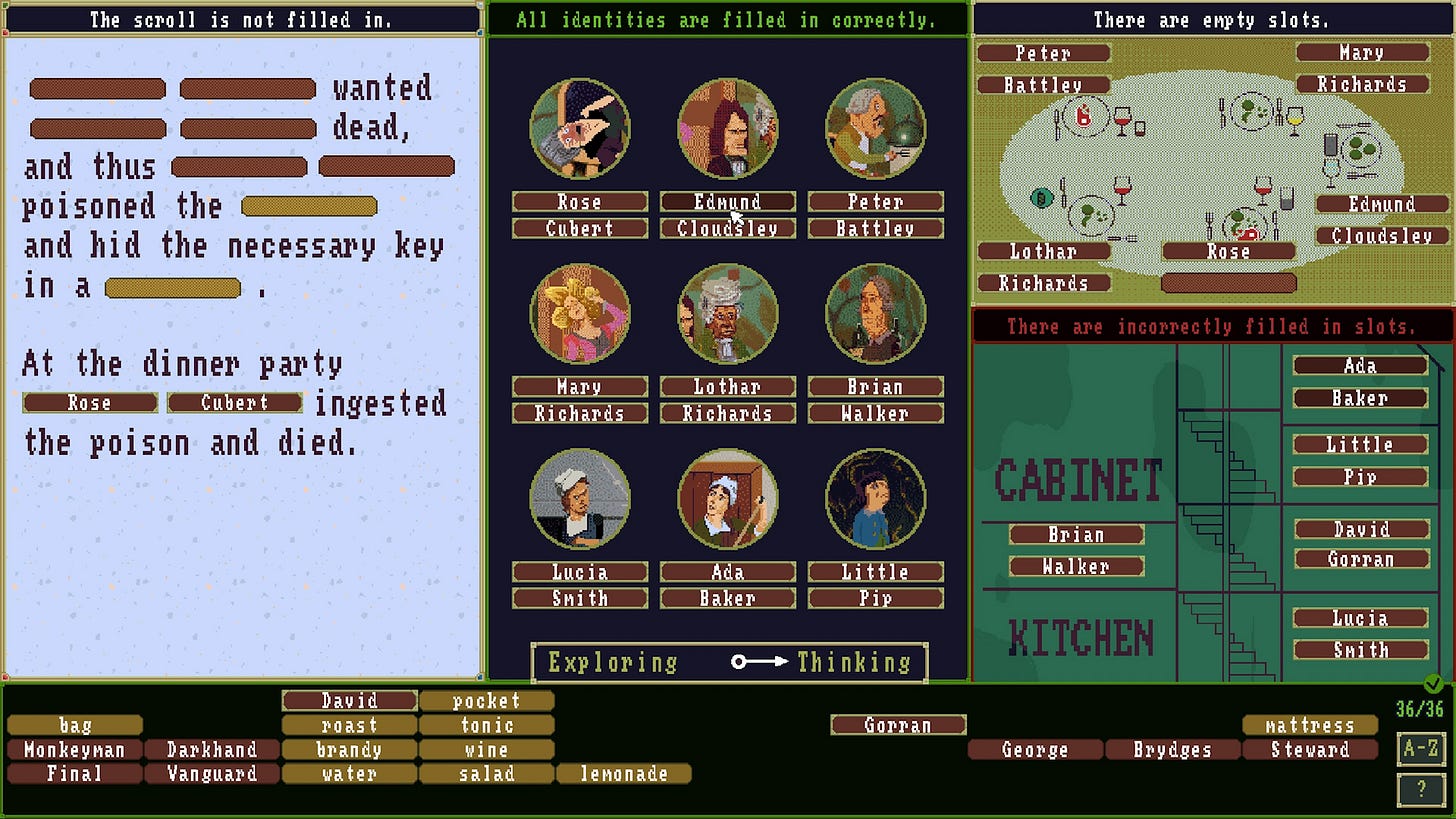

There's also Case of the Golden Idol. Here, we also explore dioramas from the moment of some poor sap's death. We can read notes, rifle through people's pockets, and bounce between different rooms - before filling out these scrolls which detail the events of the murder.

And in the upcoming Scene Investigators, currently available in demo form, we're let loose on a 3D crime scene. After rooting through this apartment we have to figure out the answers to five questions about the murder - and type them into a laptop.

Plus, the game doesn't actually have to involve a murder - or any other crime. Take Riley & Rochelle, for instance. In this game we play as a documentarian who is making a movie about two musicians. We must pour through letters, notes, tapes, and vinyl records to figure out the exact date of some key documents.

Ultimately, this deduction-style of gameplay can work in any kind of game where we must make sense of information - because while we might think of these titles as "detective games", they're really just logic puzzles. Reminiscent of some of the riddles in a Professor Layton game.

We are given some information. And we have to answer questions about that information. But the only way to get to the truth is to perform various deductive reasoning tricks.

So that might involve cross referencing multiple clues. We can establish a man's name in Golden Idol by piecing together a surname on a poster, a first name on a pocket watch, and two initials on a score sheet. Or process of elimination. If we've named two of the midshipmen on board the Obra Dinn, then we can safely arrive at the third's identity.

Or using inference and assumption. Whoever is sat in seat five at the party in Scene Investigators is the only one drinking juice instead of wine. And because Jake is referred to as a recovering alcoholic, it's probably his chair.

Contradiction Style Games

The second type is the contradiction-style game. And for this, let's look at Lucifer Within Us.

So we play as a digital exorcist, who is hunting down humans who have been tricked into doing a murder - by AI demons. Uh… stick with it.

In each crime scene we can interview a handful of witnesses and suspects - who share their testimony. Their recollection of the day is detailed in a nifty timeline at the bottom of the screen.

We'll need to use these statements to figure out the killer - but if we simply take all of the testimonies at face value, we won't have what we need to close the case. And that's because... well, people lie.

So one guy, Abraham, says he was tending the bushes all morning. But that directly contradicts the testimony of Nerissa who says she spoke to Abraham first thing.

So by presenting Nerissa's statement to Abraham, he'll fess up to his lie and amend his statement to give more detail. Do this to all the phoney statements and we'll finally have the evidence needed to accuse the correct killer.

Now this is a pretty common style of gameplay in detective games.

It's most famously seen in the Ace Attorney series, where we cross examine witnesses on the stand - and can present evidence that directly contradicts statements in their testimony.

And it's also a big part of L.A. Noire. When interviewing witnesses we have to judge if each statement is truthful or not. Sometimes we have to rely solely on body language and facial cues - but we can also use cold hard evidence to prove that someone is lying.

This time, the gameplay isn't about logical deduction - it's more like playing spot the difference. Closer to something like Papers, Please, where we need to point out inconsistencies in each traveller's documents.

So we have to carefully assess the veracity of each piece of information, and look for ways that it contradicts evidence that we know to be factual. Perhaps a suspect's alibi doesn't check out when compared to a CCTV recording. Or perhaps a witness's testimony needs to be amended because they misremembered a crucial detail.

These contradiction-style games require a keen eye and a deep knowledge of all the facts.

Investigation Style Games

The final type is the investigation-style game. For this, let me tell you about a murder case in Shadows of Doubt - a detective game that's currently in early access. My victim is Kyra Brison. She was gunned down in the hospital where she works.

Next to the body is a toy car - maybe the sick calling card of a serial killer? If so, it's a crucial clue because it has an unknown fingerprint on it: type BD.

Now, in all of the games so far, the information we need is easily accessible. Perhaps spread across two or three screens. Or contained within the testimony of two or three people. If that was the case in Shadows of Doubt we'd have this case wrapped up in minutes - just find the person with the correct prints.

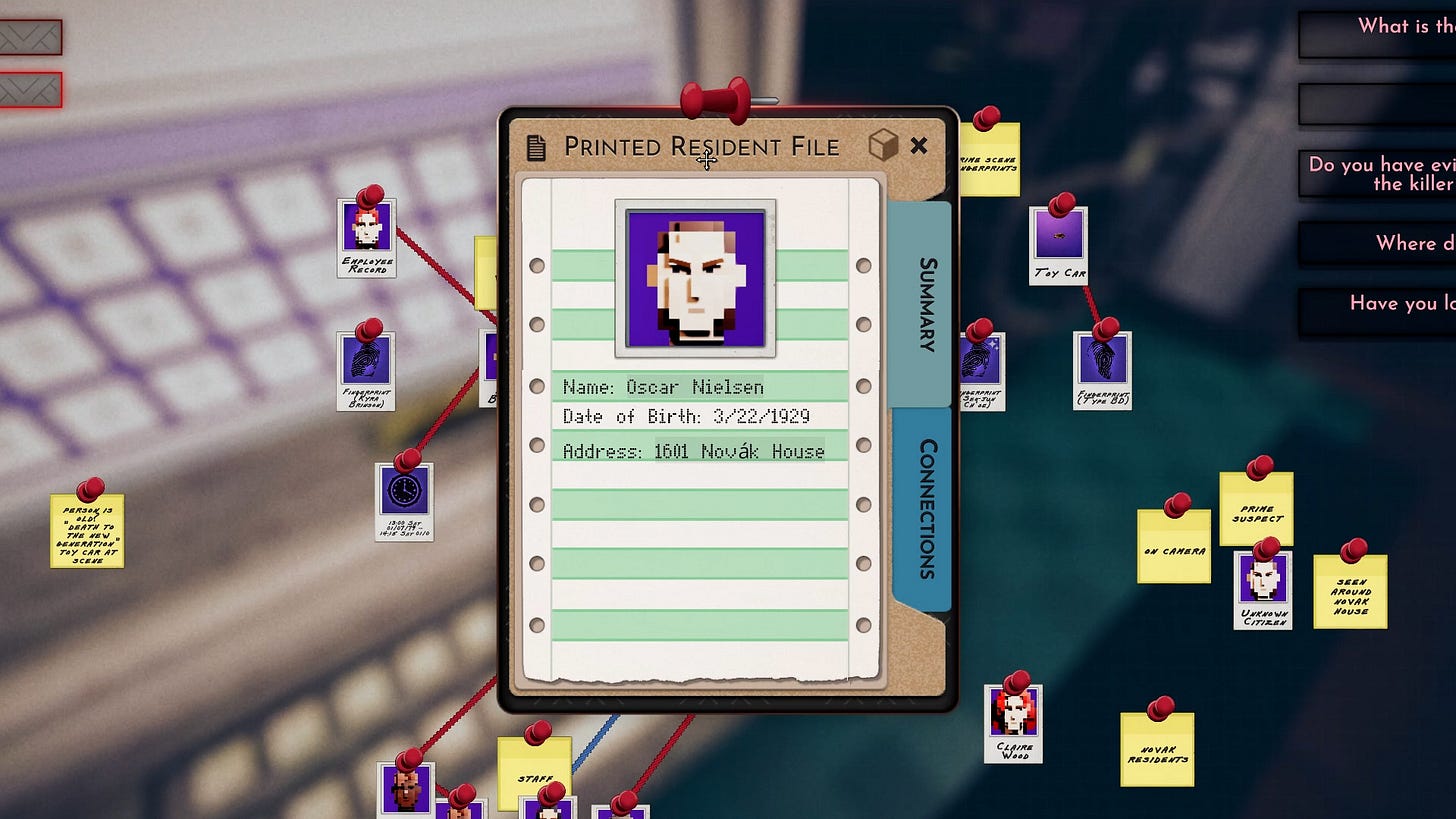

But, in this game, there are slightly more than three people. In fact, the game takes place in a densely packed city block that is populated by literally hundreds of simulated citizens. They all have homes and jobs, partners and friends, shoe sizes, blood types, and fingerprints. Finding the owner of these BD prints is going to be... difficult.

That's the crux of the investigation-style game. The game space is just impossibly large to wade through, and filled with red herrings. We could check the prints of every person in the city but it would take hours. So the real detective work comes from figuring out the best way to move through this mess. How can we find the needle in the haystack?

So, back to my serial killer with BD prints - I check the surveillance cameras at the hospital and scrub through to the time of death. There's a suspicious man skulking about.

I decide to ask Kyra's co-workers if they know him. I knock on every doctor's door and show the photo. No one knows his name, but I do keep getting the same info: he was seen at the Novak apartment block. Maybe he lives there?

I break into the security room at Novak house and log into the resident database on the computer. I make a list of every man who lives in the building. Todney Ribbs, Johannes Young, Martin Peters, Nino Arquette, Arran Smith, and then... bingo. Oscar Nielsen. It's the man in the photo.

I head up to his door. Check for prints on the handle. Bingo again - they're type BD. I knock on the door and then immediately cuff him. I check his pockets and find buckshot. I check his office. I find a shotgun. This is the one. I've found the killer.

Of course, the challenge with making this type of game is that it requires a lot of content to work. You need all the dead ends and red herrings to, essentially, hide the real answer. Like, I always wished that LA Noire let me investigate the case for myself - but that would mean letting us explore every house and building in Los Angeles. So, sensibly, the game simply tells us exactly where to go and limits us to just those locations.

Now, Shadows of Doubt achieves the seemingly impossible by leaning heavily on procedural generation: it can magic up hundreds of other citizens in seconds, in order to obscure the true criminal amongst the masses.

But the game doesn't have to be set in an actual city at all. And many titles in this investigation style use a massive database of information, or a fake internet, to construct an information space that is too big to check every nook and cranny by hand.

So that includes Hypnospace Outlaw, where we must traverse a humongous 90s-style web portal to enforce a set of rules. Or the old Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective game, where the pertinent locations are hidden in a sea of red herring addresses in a phone book.

And in Her Story, all of the information we need is contained in a database of 700-odd clips. But a clunky archive retrieval system makes it impossible to simply watch all of the clips in neat, chronological order. You might even consider Outer Wilds to be an investigation game.

So in these games, we have to think critically about how to wade through this enormous set of clues. Perhaps we can look for leads in the information we do have, and figure out how to follow them - so in Her Story, we can search for terms mentioned in the clips, or make best guesses about what words might be spoken elsewhere. Wait, did she always have a tattoo? Let me search for that...

We can also learn how the worlds are structured and organised. Knowing, for instance, that each home in Shadows of Doubt has a box with the occupant's birth certificate. Or that in Hypnospace Outlaw, it's possible to find hidden file archives on a secret server by typing in a special web address.

Sometimes we even need to think in terms of not just space - but also time. In Outer Wilds we might need to be in a specific spot at a specific moment. And in Shadows of Doubt, we can go back in time with CCTV footage - or use a person's work schedule to find the perfect time to break into their home.

The Accusation

So these three styles of game really capture distinct elements of the detective fantasy. Whether that's making logical deductions. Or interrogating a witness to unmask their lies. Or doing the more procedural side of police work.

But we're missing one key moment - the big reveal, where the detective finally accuses the killer.

So this usually crops up at some point during these detective games. Lucifer Within Us is primarily about finding contradictions, but we're ultimately trying to find enough evidence to accuse a killer - and present the means, motive, and opportunity.

Likewise, Shadows of Doubt will see us leading an in-depth investigation across the city - but we'll ultimately need to accuse someone, and present evidence that ties them to the murder. And we'll need to pick the correct killer as one of our deductions in Scene Investigators.

But there are also games that make this accusation the primary focus. Take Paradise Killer. In this one, a man is on trial for allegedly murdering a bunch of council members... while being possessed by a demon. Okay, this again. As detective Lady Love Dies, we have to figure out who the real killer is.

The gameplay involves exploring an open world island, hunting for clues, and interviewing a bunch of possible perpetrators with bonkers names like Doctor Doom Jazz and Crimson Acid. I guess it's technically an investigation-style game, but the gameplay is so straightforward when compared to something like Shadows of Doubt.

But the real draw is the accusation. At any point during the game, we can decide that we have enough evidence to make a conviction. We enter the courtroom and make our case to the judge - picking the most likely perpetrator for each crime on the docket.

We only get one shot at this, making for a dramatic, high stakes moment. And the game doesn't actually tell us if were were right or wrong in our accusation - so we'll just have to live with our decision. Or look it up on the internet.

There's also Whispers in the West - a cowboy themed detective game. Once again, we conduct a simple investigation where we try to amass as much information as possible about the case - before making an accusation.

This one ramps up the stakes by putting a ticking time limit on the evidence gathering - and it also lets us play in co-op with three other pals so we can confer, compare notes, and, uh, bicker about who has the best explanation for the crime.

Designing the “Tester”

So these games capture every moment of a typical crime-solving case: gathering evidence, interrogating witnesses, following leads, making deductions, and accusing suspects of deadly crimes.

But I don't think that's really what makes them detective games.

Instead, it's that all three types of game ask you to think about information in a way that a detective might. To be observant of your surroundings, and then to think critically about the clues and leads you find. To make deductions, spot contradictions, and forge connections.

Detectives are famous for their intellect and perception. Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle has said that a detective has little more than "an alert acuteness of mind to grasp facts and the relation which each of them bears to the other."

Basically - they're a smarty pants. And these gameplay structures make us feel smart too.

But that only works if the designers are smart about how they ask the player to input their answer. What I mean by that is that pretty much every detective game needs some way for the player to prove to the game that they've figured something out. To prove that they spotted the connection or made the deduction. Some kind of "tester".

And it's really easy to slip up here - and actually ruin the puzzle through the design of this tester.

Like, let's go back to that moment in Obra Dinn where we had to figure out this mystery man's identity - and consider different ways of asking the player to provide their answer.

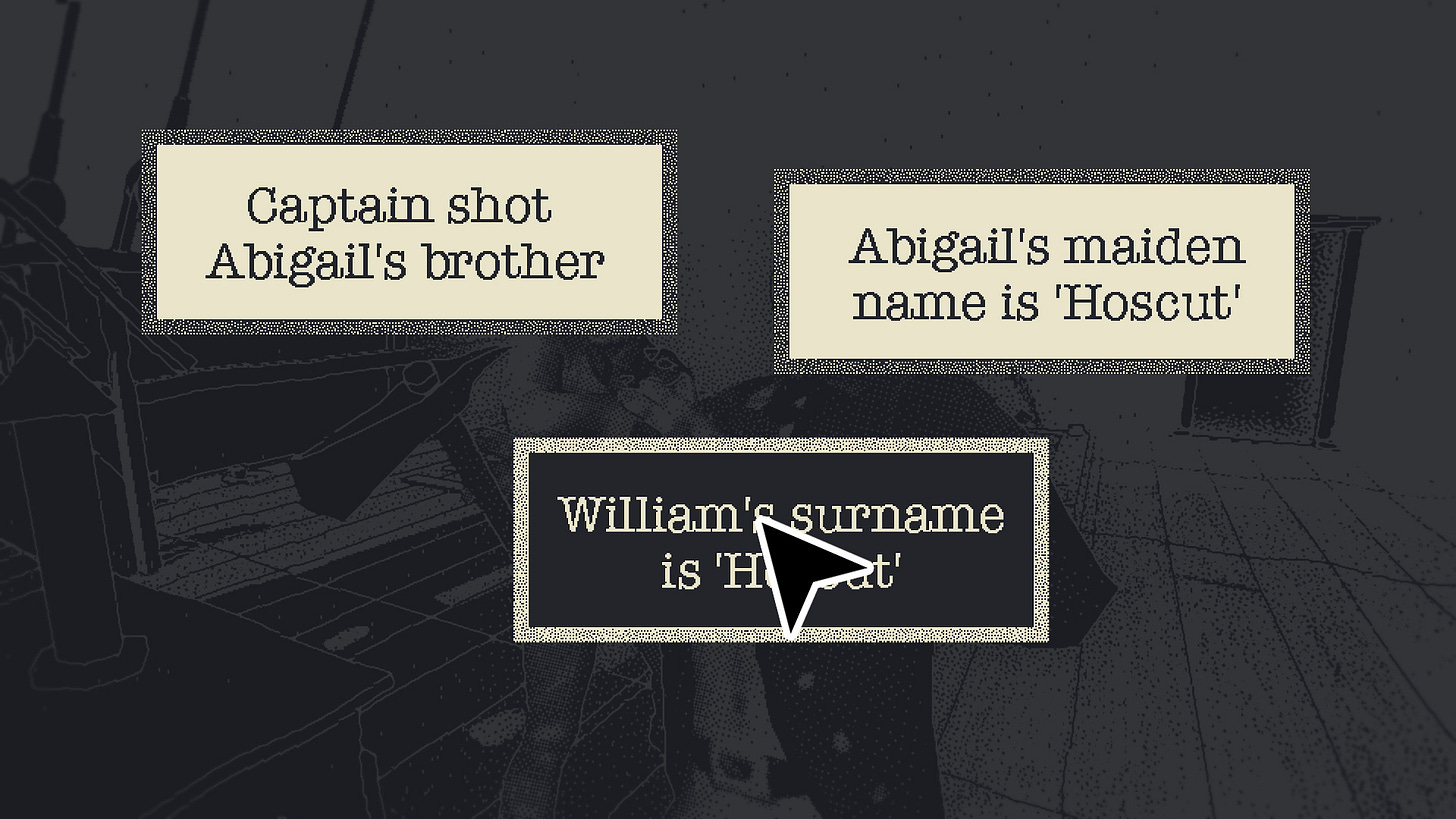

Perhaps we could have our in-game investigator create an inventory of thoughts. Like "Captain shot Abigail's brother", "Abigail's maiden name is Hoscut", and "William's surname is Hoscut". Then the player can link these clues together to create a deduction.

It's a nice gamified simulacrum of thinking - but it totally gives the puzzle away! If the player hadn't yet made the connection between Abigail and William... well they certainly will now.

And if they had made that connection... putting it on screen like this can feel patronising, and discourage critical thinking in the future. Why bother if the game is going to do all the hard work?

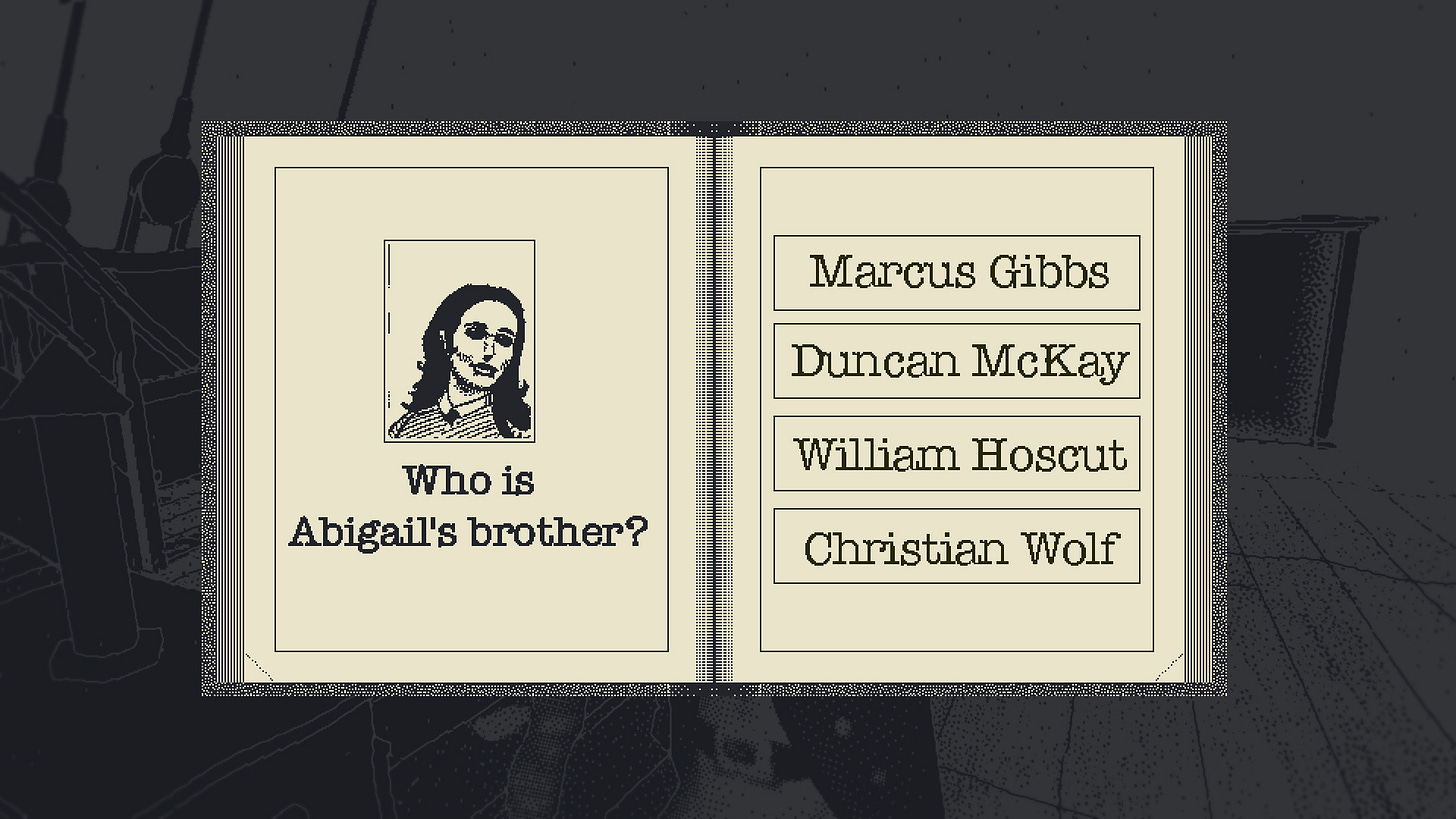

So perhaps we could ask the player a question, like "who is Abigail's brother", and then provide four possible choices to pick from.

It's a nice and simple way for the player to provide their answer... but again, it totally gives the game away.

The text of the question spoils the line of thinking that the player should be on. And by providing just four answers, we can narrow our thinking to just these possibilities. Or just pick the most plausible from the list. Or just guess! And if we don't guess correctly, simply guess again until we brute force our way to victory.

Obra Dinn does not do any of this stuff. Instead of providing leading questions that prompt the player, it asks the same generic questions for everyone on board: who are they and what is their fate?

Instead of giving the player clues that they can combine and connect in a UI, it trusts players to write things down on a notepad - meaning it's up to them to figure out what's relevant, and how those facts can be interpreted or connected.

And instead of giving the player a handful of choices, it lets them pick from any of the 60 crewmates - making it basically impossible to guess. And because we need to actually establish three correct fates before the game confirms our thinking, it's also impractical to brute force our way to victory.

So in Obra Dinn, the design of the tester means we aren't prompted or led - and we can't guess or brute force. We have to figure it out for ourselves.

And it's the same across most of these other detective games. In the deduction-style Riley & Rochelle we need to pick a complete date for each document - meaning that there's thousands of possible answers. You can't guess that.

And in investigation-style games like Shadows of Doubt, the sheer size of the game space means its near impossible to just stumble upon the right place or person by chance - you need to run the investigation and make intentional choices about where to go - and when.

And I think this is why contradiction-style games are usually my least favourite of the three, because you often can just tediously try every piece of evidence on every single statement until you uncover all of the lies.

So. The design of these testers makes for games where players have to think about information like a detective - and the game won't move on until they do. Which can lead to a truly electric Eureka-style moment of satisfaction when you figure it out.

But... it also means you're completely stuck if you don't.

Assisting the Player

So let's look at how these games subtly - or not-so-subtly - assist players in their investigations.

For one, the questions posed by the game are often extremely straightforward and specific. Like, during development, Golden Idol actually let players form full sentences to describe the events of the murder - but it was impossibly overwhelming to play. It was better, the devs found, to focus on much more clear and unambiguous questions. They shouldn't be leading - but they also shouldn't be vague.

Two, these games ramp up in complexity over time. Riley & Rochelle starts with just a few notes and simple logic puzzles - but in later chapters we'll have to juggle loads of clues and figure out more complicated, multi-step deductions.

Three, the games provide multiple avenues to reach the right answer. In Obra Dinn there are often multiple ways to deduce an identity, so you don't have to rely on one specific clue. In Shadows of Doubt, a killer can be traced in many different ways - from footprints to fingerprints to CCTV footage to telephone call history. And in Hypnospace Outlaw, if you can't figure out a clever way in, you can sometimes just farm for currency and pay to get access.

Four, the games give players small victories, by giving step-by-step confirmations. In Golden Idol we get confirmation for every panel we figure out - rather than having to solve the entire case in one go. That would be a lot less manageable.

Five, these games provide useful tools. Sometimes all we need is a notepad and pen, but I love the pinboard system in Shadows of Doubt. You can place any person, place, or object on the board, make connections with string, and even write custom notes. It makes investigations, like, 10 times more fun.

Elsewhere, Her Story lets you tag footage and Hypnospace Outlaw lets you bookmark useful sites.

And six, these games provide useful hints. Obra Dinn lets us know when we have access to enough information to fill in a character's fate. If we can't track a killer in Shadows of Doubt they'll eventually kill again, giving us more leads to follow. And in Golden Idol we can simply unlock written hints - as long as we can get through an intentionally-tedious mini-game.

Other Games

Now look: there are some great detective games that don't really fit into these categories at all.

Take, for instance, Overboard, which is a sort-of reverse detective game. You play as a murderer who has just offed her husband and now needs to falsify evidence, construct an alibi, and throw suspicion onto someone else.

Or Silicon Dreams, a cyberpunk interrogation game where you're basically doing the Voight-Kampff test on a bunch of androids. You talk to these bots - but instead of looking for contradictions and lies, you're actually assessing their emotional response to your questions. And you can even manipulate their emotions to make the androids more talkative. If this bot isn't playing ball, maybe slap the cuffs on them to scare them straight.

And what about Among Us? That's totally a detective game, right? But the killer is another player, and the team of detectives have to figure out who is telling the truth, and whose alibis don't stack up.

So, the book is certainly not closed on the question "what makes a good detective game?". But in this post I hopefully showed one very effective way to do it. Basically - give the player clues and information. Ask them to think about it critically, by making deductions, looking for contradictions, forging connections, or making accusations. And then test them on their thinking in a way that doesn't prompt or lead the player - or allow for guessing or brute force.

This will make players think like a detective - and have the same potent thrill of piecing together the mystery. But could be many different ways to achieve that same goal. So maybe I'll come back in another five years and see how this genre has evolved by then.